Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, to be published this September by the History Press, Inc. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

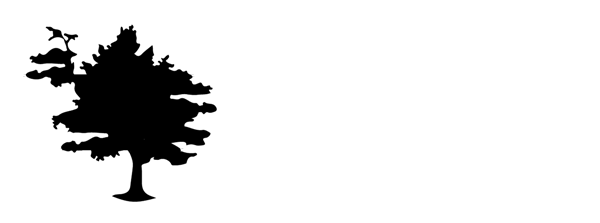

One of the country’s most sophisticated scientific laboratory complexes, the National Bureau of Standards, once stood on a hill off of Connecticut Avenue at Upton Street, in the serene, semi-rural upper Northwest section of the city. Through much of the 20th century, this secluded and unassuming enclave quietly made countless important contributions to the safety and quality of the manufactured goods we take for granted today, including everything from airplane engines to kitchen crockery.

Connecticut Avenue runs along the top of this circa 1930 view of the Bureau’s campus (Author’s collection).

The Bureau was founded in 1901, during a period of burgeoning industrial production and dramatic technological change. Telephones, automobiles, light bulbs, electrical machinery—it all needed practical, reliable standards based on methodical scientific testing. The new Bureau filled this need, greatly expanding on the mission of its predecessor, the Office of Weights and Measures, which had been set up in the Treasury Department in the early 19th century to ensure that standard measures were used when calculating customs duties on imported goods.

First housed temporarily in the old Office of Weights and Measures building on Capitol Hill, the fledgling Bureau in 1901 urgently needed space to build its own laboratory. The requirements were exacting. The laboratory had to be well outside the city proper, somewhere completely free from vibration, traffic disturbances, and the electrical interference caused by streetcar lines. It had to be solidly built, using twice the construction materials of an ordinary office building, heating and plumbing lines that were twice as complicated as an average building’s, and four or five times the usual amount of wiring. Some labs were to be fitted out with both running salt water and fresh water as well as dispensed crushed ice. Ancillary buildings would also be needed for engines, pumps, heavy machinery, and the fabrication of sensitive scientific instruments. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, to be published this September by the History Press, Inc. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

One of the stateliest private buildings in Washington is the old Masonic Temple at 13th Street and New York Avenue NW, completed in 1908 and now home to the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Like other Masonic temples, the imposing structure was built with unique cross purposes; it was meant to be both a public forum for lectures and performances as well as a private place for the fraternal order’s meetings and rituals. Since the 1980s, this distinctive Renaissance Revival palace has had a remarkably fitting second life as a museum, and now the NMWA is looking to preserve the building for many more years with much-needed roof repairs. As a participant in the Partners in Preservation program, the museum will be hosting a festive open house this Sunday, May 5, from 12 to 5, offering a great, free opportunity to see this extraordinary building up close and appreciate the art it now displays.

Photo by the author.

The sharp-eyed visitor will notice decorative touches denoting the building’s original use as a Masonic Temple. Freemasonry is a centuries-old tradition descended from medieval stone masons’ guilds, although modern masons are a strictly fraternal order dedicated to benevolent acts. Masons organize themselves into lodges, which are chartered by regional Grand Lodges. DC got its own Grand Lodge in the mid 19th century. In 1870 it built a temple, still standing, at 9th and F Streets NW, but by the 1890s, with 49 Masonic lodges chartered throughout the city, the old hall was no longer adequate. The Masons resolved to build a magnificent new temple at a suitably prestigious location.

The site selection committee received some 20 offers for sites all around the city, and in 1899 they chose the distinctive trapezoidal corner lot formed by New York Avenue, 13th Street, and H Street NW, a prominent location that would allow unobstructed vistas of the new temple on three sides. The lot, once a knoll with a clump of trees known as “Seven Oaks,” cost $115,000.

Continues after the jump. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. A version of the following article will appear in Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, to be published this September by the History Press, Inc. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Of all the mid-20th-century icons of everyday life in Washington, Hot Shoppes ranks among the most memorable. The chain of casual drive-in restaurants founded by J. Willard “Bill” Marriott (1900-1985) in 1927 once had a commanding presence at dozens of sites across the metropolitan area, serving up thousands of fast, friendly meals every day. Beginning with a tiny root beer stand in Columbia Heights, the chain rose rapidly to prominence in the 1930s, expanded in the 1940s and 50s, and then almost as dramatically dwindled away in the 1970s and 80s, eventually slipping into history after winning the hearts and stomachs of several generations of Washingtonians.

Matchbook cover from the early 1960s (Author’s collection).

The Marriott rags-to-riches story used to be one of the most oft told in the city. The son of a Utah sheep rancher, Bill Marriott was imbued at an early age with strong Mormon beliefs and an intense work ethic. As a teenager he experienced firsthand how hard it was to make a living raising livestock out west and resolved to get into a line of business less subject to market volatilities. In September 1921, after spending time in New York, Marriott passed through Washington on his way home to Utah. He spent a day sightseeing and noticed how vendors of ice cream, lemonade, and soda would sell out to the sweltering crowds practically as soon as they arrived on the scene with their carts. Six years later, when he was ready to start out on his own, Marriott decided to return to Washington to open a franchise selling A&W root beer.

The original Hot Shoppe on 14th Street (photo courtesy Historic Photographs collection, Marriott International Archives).

With a partner from Utah, Marriott rented out a slim corner storefront at 3128 14th Street NW in the Arcade Market, where the DC-USA shopping center now stands. Inside was a counter with nine stools. Offering frosted mugs of cold root beer for a nickel, Marriott did a booming business. Within a few months, he had gone out to Utah to marry his college sweetheart, Alice “Allie” Sheets (1907-2000), driven her back to D.C. in his rickety Model T, and opened his second root beer stand downtown at 606 9th Street NW, another resounding success. While Allie counted the nickels every evening, separating the ones stuck together with root beer syrup, Bill would wrestle with problems like how to keep expensive frosted mugs from shattering when they were plunged into boiling water to be sanitized. (With the help of well-connected friends, he was able to get D.C. regulations changed to allow cool chlorine-based sanitization.)

Continues after the jump. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Washington has one of the highest concentrations of apartment dwellers among American cities, and fortunately many of its historic apartment houses from the early decades of the 20th century have survived. Among these, the Northumberland, opened in 1910 at 2039 New Hampshire Avenue NW, is one of the best preserved. Thanks in part to its very early conversion (1920) to cooperative ownership, the building has benefited over the years from the meticulous care and attention of farsighted owners and remains a jewel-like oasis of turn-of-the-century urban living.

The Northumberland (photo by the author).

The Northumberland was one of many projects undertaken by the relentlessly energetic Harry Wardman (1872-1938) in the early years of his career when he was building row after row of houses in Mount Pleasant and Columbia Heights and just starting to construct towering apartment houses. “In apartment building the most expensive structures in the city are the work of Mr. Wardman,” the Washington Times noted in 1911, soon after the Northumberland was completed. Wardman was a developer’s developer, putting up the most desirable buildings possible at the least possible cost and then quickly moving on. “His money is always active and he is always borrowing,” the Times explained. “He always takes profits and goes at something new.”

Continues after the jump Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Recent news articles about the Washington Post’s plan to sell its headquarters building have occasionally mentioned the newspaper’s historic home, which once stood at 1341 E Street NW on Washington’s old Rum Row. While the newer building has witnessed some of the newspaper’s greatest journalistic achievements, its plain and functional architecture is a far cry from the Post’s old building, which was one of the finest and most ornate Romanesque Revival structures ever built in Washington.

The Post Building is on the left in this circa 1908 postcard (author’s collection).

The E Street building was the Post’s fourth home. The paper began in 1878 when Stilson Hutchins (1838-1912), who had previously founded the St. Louis Times, came to Washington to start up a Democratic Party organ in the Nation’s Capital. His new daily first set up shop in the former headquarters of the Washington Chronicle at 914 Pennsylvania Avenue NW but moved within a year to Jackson Hall, at 339 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, a prominent Greek Revival structure where the Congressional Globe had been printed for many years. From here, Hutchins planned the first building specially designed for the Post, at 10th and D Streets NW, which the newspaper occupied beginning in 1880.

Continues after the jump. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Interior of the Water Gate Inn (author’s collection).

One of the most distinctive restaurateurs of 20th century Washington was Marjory Hendricks (1896-1978), owner of the Water Gate Inn, which she operated from 1942 to 1966 on the current site of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Like all great restaurateurs, Hendricks knew how to keep her guests charmed and entertained, and her Pennsylvania Dutch-inspired eatery was unique in Washington history.

Born in Seattle, Hendricks came to the D.C. area with her family in 1918. After a brief first marriage and early restaurant experience in Reno, Nevada, Hendricks traveled to France in 1929 to study cooking. On her return in 1931, she acquired a failing country club in Rockville, Maryland, which she turned into the Normandy Farm restaurant, a rustic inn of the type that were very popular in the era. The restaurant remains in business today, its name spelled slightly differently.

Eleanor Roosevelt was among the Washingtonians who discovered Normandy Farm, and she is said to have encouraged Hendricks to open a “branch” restaurant in D.C. In 1941 Hendricks bought the former Riverside Riding Academy at 2700 F Street NW as the site for her new in-town eatery. The location was something of a gamble: the Foggy Bottom neighborhood was a semi-industrial backwater at the time. Some even called it a slum. It was far away from most of the city’s established nightlife, although across the street stood another former riding facility that had been turned into a supper club, The Stables. Nevertheless, with the tremendous influx of newcomers to the city at the beginning of World War II, existing restaurant facilities—particularly for large groups—were inadequate, and a talented restaurateur like Hendricks was in high demand wherever she might choose to set up shop. Wartime materials shortages kept her from opening the new place until August 1942, after which it soon became a hit with local diners.

Continues after the jump. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

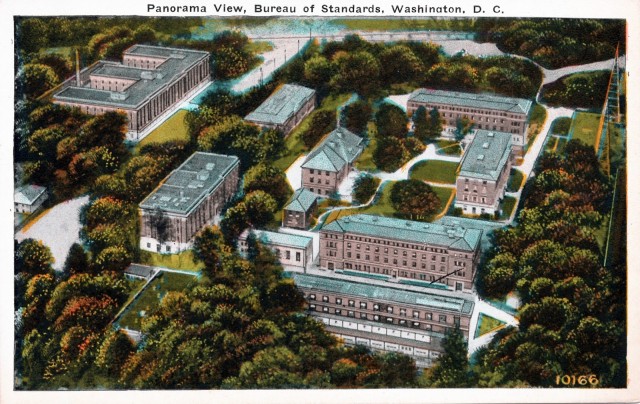

“Why is peace such an untellable tale?” wonders one of the patrons in a Berlin library as he is observed by a kindly angel in Wim Wenders’ classic film, Wings of Desire (1987). Just as peace is hard to write about, so it seems to be hard to erect a memorial to. We have countless monuments to wars and their heroes, but relatively few to celebrate peace. Even our Peace Monument, erected in 1877 at the foot of Capitol Hill where Pennsylvania Avenue ends, is really more about war than peace, and like the city’s many war memorials, people have bickered over it at least as much as they’ve celebrated its theme of tranquility.

The Peace Monument (photo by the author).

The monument was the brainchild of Admiral David D. Porter (1813-1891), one of the top two naval commanders of the Civil War. In 1864 Porter had led the successful naval campaign to take Fort Fisher at Wilmington, North Carolina, in what would be the last major naval campaign of the war. It was after the fall of Fort Fisher that Porter began a campaign to have a memorial erected to all of the brave Navy men who had been killed in the war, just as his famous father, War of 1812 hero David Porter (1780-1843), had commissioned the first naval monument to heroes of the Barbary Wars. That memorial, now known as the Tripoli Monument, had been completed in 1806 and originally stood in the Navy Yard but was moved to the Naval Academy in Annapolis in 1860.

When the Civil War ended, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles (1802-1878) made Porter superintendent of the Naval Academy, where he would go on to institute many reforms that enhanced the professionalism of the navy. While at the Academy, Porter worked to get the new naval monument built so that it could join the venerable Tripoli Monument at Annapolis. He collected contributions from Naval officers and seamen totaling $9,000 and sketched out the design of the monument himself. Sculptor Franklin Simmons (1839-1913), who also sculpted the equestrian figure of General John A. Logan at the center of Logan Circle, was hired to carve the figures for the monument in fine white Carrara marble in his studio in Rome. So far so good. A reading of the National Register listing for Civil War monuments in Washington suggests that the ensuing production of the memorial was accomplished with efficiency and purpose: “The sculpture was erected by the government with contributions from Navy personnel under a Congressional Act approved July 31, 1876 (19 Stat. 114). It was sculpted and carved in Rome in 1877 and dedicated in the same year.”

The Peace Monument c. 1880, from a stereoview in the author’s collection.

However, things didn’t really go quite that smoothly. For one thing, it seems that Admiral Porter and Secretary Welles may not have gotten along well together. According to retired Navy officer C.Q. Wright, who wrote about the Peace Monument in the Washington Post in 1923, “the few surviving letters which passed between [Porter and Welles] concerning the location of this monument seem to indicate indifference in the mind of Mr. Wells to the erection of the monument or a quiet disapproval of the affair in which he may have thought he saw sign of the high-handed self-assertion of Admiral Porter.” Wright suggests that friction between Porter and Welles may have led to changes both in where the memorial was to be placed and how it was to be designed.

Continues after the jump. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

The retail enterprise founded by Julius Garfinckle (1874-1936) in 1905 was a relative latecomer to the city’s department store field. Woodies, Lansburgh’s, the Palais Royal, Kann’s, Goldenberg’s, and Hecht’s all were established by the 1890s, making for a saturated and highly competitive market by the turn of the new century. But Garfinckle’s store (he later changed his and the store’s name to Garfinckel) carved out a unique, high-end niche and held on to it for 85 years, cultivating generations of dedicated shoppers who depended on the store for the trendiest and classiest apparel. When Garfinckel’s finally declared bankruptcy and closed in 1990, it was a heart-wrenching experience for employees and customers alike.

The former Garfinckel’s building as it appears today (photo by the author).

Born in Syracuse, New York, Garfinckle went to Colorado as a young man, hoping to strike a fortune in silver mining. Instead he became a clerk in a dry goods store. He moved to Washington in 1899, where he found employment with Parker, Bridget & Company, a prominent fashion-oriented dry goods store at 9th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW. As a buyer for that store’s women’s clothing department, Garfinckle traveled frequently to New York and learned all the ins and outs of the retail fashion industry.

In 1905 Garfinckle set out on his own with the founding of his namesake store, which occupied the bottom floor of a seven-floor building at 1226 F Street NW. With his Parker Bridget experience and contacts, Garfinckle was able to fill his new store with “a carefully selected stock of women’s suits, cloaks, furs, &c, together with imported novelties and specialties,” according to the Washington Post, which observed that the new store’s “popularity is already assured.” In keeping with the expectations of his high-end customers, Garfinckle made sure that each received exceptional personal attention.

Garfinckle’s original store (Source: DC Public Library, Star Collection, © Washington Post).

The Post’s early prediction of success soon came true. Garfinckle’s gradually filled all seven floors of its host building, an odd-looking structure that was originally half-built to allow for future expansion. Within a few years Garfinckle’s booming business led him to take over the two-story space on the corner previously occupied by Brentano’s bookstore and then to build out the missing floors above it.

But even that complete building wasn’t big enough, and by the 1920s, after Garfinckel changed the spelling of his name, he had his sights set on constructing a grand new building better fitting his prestigious business. He began assembling as much property as he could at the northwest corner of 14th and F Streets NW, and in 1928 announced plans for an imposing new 8-story building.

Like many a modern-day developer, Garfinckel immediately ran afoul of the city’s zoning regulations. He had planned for the full 130-foot elevation of his building to extend out to the property line, but new zoning rules adopted in 1927 required a setback for the floors above 110 feet. Protesting the requirement, Garfinckel’s attorneys pointed out that the newly-completed National Press Building, located cater-corner to the site, had no setback. However, that building had been completed in 1927, just before the new rule took effect. When finally constructed, the Garfinckel building dutifully included the required setback.

Continues after the jump. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Union Station probably reflects better than any other single Washington building the remarkable self-assuredness and imperial aspirations of its age. The architecture is stunningly elegant, both outside and in, and it was one of the first properties in the District of Columbia to be named to the National Register of Historic Places. After having been brought back from near-death in the 1980s, the station is once again the subject of development debate. Instead of dreaming up improbable and unneeded functions like the ill-conceived National Visitor Center of the 1970s, planners are now focusing on the hard realities of the station’s increasingly heavy use as a transportation hub, which strain its resources and demand modernization. A vision of an almost unrecognizably transformed space has been put forth.

Photo by the author

While the feasibility of this multi-billion dollar plan is debated, a more immediate proposal is on the table to make alterations to the station’s main waiting room (primarily by cutting two escalator holes in the floor) to allow visitors to more easily access the retail space that has been created in the basement. Repairs have also been underway in the main waiting room and surrounding areas as a result of damage sustained during the 2011 earthquake. All of this activity raises questions about how well the station’s grand interior spaces have been preserved and whether it is time to revisit compromises made back in the 1980s. Most notably, a few of the building’s finest public spaces—the Ladies’ Waiting Room, the Lunch Room, and the Smoking Room (or Men’s Waiting Room)—suffered in the 1980s rehab and could once again be grand if finally given the chance.

To the casual observer hurrying to catch a train, it would appear that Union Station’s interior has been carefully preserved, and in many ways this is true. A group of architects and developers, including Benjamin Thompson & Associates, who had worked on Boston’s Faneuil Hall and Baltimore’s Harborplace, as well as Harry Weese & Associates, who had designed the Metro system’s stations, collaborated on the redevelopment under many watchful eyes, including those of the National Park Service and the D.C. Historic Preservation Office. Painstaking attention was paid to bringing the building’s four most prominent public rooms—the Main Waiting Room, West Hall, Dining Room, and Presidential Suite—back to something close to their original appearance. Approximately seven pounds of 22-karat gold were applied as leaf to the 320 octagonal coffers that line the main waiting room’s vaulted ceiling. The original white marble floor, long since replaced and cut into for the visitor center, was carefully reconstructed. Plaster everywhere that had suffered deterioration and water damage was meticulously restored. Original wall colors, buried under twenty-two layers of paint, were recreated, as were delicate murals in the former dining room. The entire effort, from 1985 to 1988, was widely acclaimed as a preservation success.

Continues after the jump. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

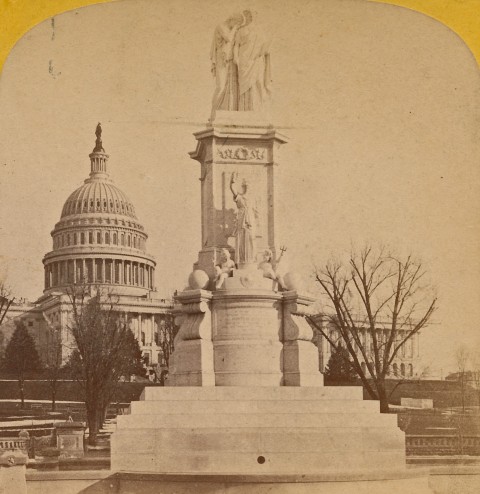

The story of S. Kann, Sons & Co., once Washington’s second largest department store behind Woodward & Lothrop, begins just north of us in Baltimore. There a German immigrant named Solomon Kann (1836-1908) opened a clothing store during the Civil War. As time went on, he brought his three sons—Louis Kann (1860-1920), Simon Kann (1861-1932), and Sigmund Kann (1865-1930)—into business with him. In the early 1890s, the family learned that a Washington, D.C., clothing merchant by the name of Dorsey Carter wanted to sell his business, and Solomon Kann sent Louis and Sigmund to investigate. The sons bought the stock of the old business and later two other nearby stores as well, combining their offerings and opening S. Kann, Sons on the northeast corner of 8th Street and Market Space NW in 1893. The location was perfect, right in the heart of Washington’s commercial district, directly across Pennsylvania Avenue from Center Market (where the National Archives now stands). Louis (called “short, quick, and aggressive” by the Washington Post) and Sigmund (“tall, deliberate, and reserved”) soon brought Simon (“short, stocky, and wearing thick-lensed spectacles”) in as well, and the brothers’ store prospered under their energetic management.

Kann’s Busy Corner in 1907 (author’s collection).

Kann’s, like Woodies which had preceded it by only a few years, was one of the new breed of progressive department stores, imbued with radical business policies: goods were offered at a single, fixed price—no haggling—and customers were welcome to return goods they didn’t want and have their money cheerfully refunded, something previously unheard of. Kann’s and Woodies both vigorously promoted the “customer-is-always-right” philosophy, and it paid off in booming sales, which allowed them to keep prices low. Kann’s in particular was committed to selling goods at the lowest price possible, even resorting to shaving prices to various fractions of a cent—two thirds, three quarters, seven eights—a tactic that had a powerful psychological effect on price-conscious shoppers. “Always the best of everything for the least money,” Kann’s advertised.

Kann’s circa 1935 (Source: Library of Congress).

Frances Folsom Cleveland (1864-1947), the stunningly attractive first lady who had returned to the White House with her husband in 1893 for his second term, was an early customer of Kann’s. According to the Washington Post, “Washington was eager to see and admire her as she drove about the streets in the highly polished White House landau, drawn by a fine team of horses, attended by a coach and footman, visiting many of the stores along the avenue.” The story goes that as she shopped at Kann’s she attempted to have her purchases charged to her account, just as she did everywhere else, only to be informed by the nervous clerk that Kann’s policy was strictly cash-and-carry. Fortunately, Mrs. Cleveland had sufficient funds to cover her purchases and took no offense. The bargains at Kann’s were worth it.

Continues after the jump. Read More