Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Washington has one of the highest concentrations of apartment dwellers among American cities, and fortunately many of its historic apartment houses from the early decades of the 20th century have survived. Among these, the Northumberland, opened in 1910 at 2039 New Hampshire Avenue NW, is one of the best preserved. Thanks in part to its very early conversion (1920) to cooperative ownership, the building has benefited over the years from the meticulous care and attention of farsighted owners and remains a jewel-like oasis of turn-of-the-century urban living.

The Northumberland (photo by the author).

The Northumberland was one of many projects undertaken by the relentlessly energetic Harry Wardman (1872-1938) in the early years of his career when he was building row after row of houses in Mount Pleasant and Columbia Heights and just starting to construct towering apartment houses. “In apartment building the most expensive structures in the city are the work of Mr. Wardman,” the Washington Times noted in 1911, soon after the Northumberland was completed. Wardman was a developer’s developer, putting up the most desirable buildings possible at the least possible cost and then quickly moving on. “His money is always active and he is always borrowing,” the Times explained. “He always takes profits and goes at something new.”

Continues after the jump

The Northumberland circa 1914, before the roof crest was removed (click to enlarge. Author’s collection).

Along with the Dresden Apartments at Connecticut Avenue and Kalorama Road NW, the Northumberland was one of the first large apartment buildings Wardman built. It was designed by Wardman’s chief architect at the time, Albert Beers (1859-1911), who had moved to Washington in about 1903 after many successful years in Bridgeport, Connecticut. For the Northumberland, named after Wardman’s home county in England, Beers designed an eclectic Georgian Revival building with features evocative of Italian Renaissance architecture. The façade is divided into three roughly equal bands (in many Classical Revival buildings the middle band is much taller than the top and bottom bands), and it is finished in tapestry brick and pressed brick with Indiana limestone trim. The unusually large windows make for airy, light-filled apartments. The front entrance is framed by an impressive columned portico, and a forceful, heavily modillioned cornice rings the roofline. The one major change to the exterior of the building was the early removal (sometime around 1920) of the original medallioned crest on top of the cornice.

The Northumberland circa 1920, after removal of the roof crest (Source: Library of Congress).

Located on New Hampshire Avenue just a block to the east of 16th Street and immediately south of Meridian Hill, the Northumberland was in one of the city’s hottest residential neighborhoods when it was new. Led by the powerful Mary Foote Henderson (1846-1931), 16th Street property owners and investors vied bitterly with their Massachusetts Avenue counterparts to bring the wealthiest and most prestigious residents and their most extravagant mansions to what was briefly called the Avenue of the Presidents. Mrs. Henderson probably would have preferred palatial mansions to large apartment houses, and, according to Kim Williams, she didn’t think much of Wardman, the brash young Englishman who was building everything up. But, as Northumberland board member Richard Cote explains, Wardman tried to meet Mrs. Henderson’s vision for the neighborhood in the elegant design and construction of the Northumberland, which would remain one of his most decoratively rich projects. Well-to-do upper middle class Washingtonians soon filled the new apartment house.

The lobby and main staircase (photo by the author).

One VIP to move in to the Northumberland early on was Chief of Police Maj. Richard H. Sylvester (1860-1930), known as the father of modern police professionalism. Sylvester quickly restored peace and quiet to what had become a noisy early-morning routine at the Northumberland. As the Washington Post reported in September 1910, tradesmen were in the habit of making early morning deliveries via the alley that ran along the back of the building: “Ice men have been in the habit of rattling up to the back entrance and chopping ice for their customers. Milkmen have been banging their bottles, laundrymen bumping their baskets, and grocery men dumping boxes off their wagons. As a result of the various activities of these energetic tradesmen, pandemonium reigned just about the time some of the tenants were most enjoying their sleep.” After a rude awakening the first morning he spent in the building, Major Sylvester had an officer from the 8th precinct stationed behind the building to prevent deliveries before 8am. Problem solved.

One of the two decorative fireplaces in the lobby (photo by the author).

The Northumberland’s lavishly decorated lobby—one of only 15 interior spaces in D.C. that are designated as historic landmarks—evokes the atmosphere of an English hunting lodge with its connotations of upper class refinement and a life of leisurely diversions. The walls and stately Corinthian columns have a warm, faux-marble finish and are handsomely framed by black base trim. On either side of the entrance are waiting areas with elaborately decorated fireplace mantels, again finished to look like warm Sienna marble and surmounted by heraldic flags and arms that appear to be carved in stone (they are actually scagliola plaster). The main staircase in the center of the lobby leads up to a rounded landing where three stained-glass windows let in warm, colored light and lend a quaint atmosphere to the space.

Originally the building had 68 apartments ranging from efficiencies and one-bedroom “bachelor” apartments to three-bedroom “housekeeping” apartments. They tend to be light and spacious with sometimes unusual layouts as they spill around the C-shaped building. The floors are finished in parquet “wood carpeting,” made up of contrasting red and white oak segments with mahogany border strips. Many apartments still have their original built-in wall safes, and some also still have the faux fireplace mantels that were installed in each unit. Like all apartment buildings of that era, the Northumberland included these faux fireplaces to give residents the feeling that they were living in a house. Elegant chandelier-like light fixtures were also standard at the Northumberland, and many still remain.

A faux fireplace in a Northumberland unit (photo by the author).

In keeping with his modus operandi, Wardman sold the Northumberland within a few years of its opening, and it was sold again several years after that. In 1920, the building’s third owners, developers Clarence Calhoun and James Sharp converted the building to a cooperative, selling it to an association of owners for $480,000. Cooperatives were not new at the time. According to James Goode, the first cooperative in the city had been the Concord, constructed in 1892 at New Hampshire Avenue and Swann Street NW (and demolished in 1962). However, they were still “more or less of an experiment in Washington,” as described by the Washington Post. Another very active developer, Allan E. Walker (1880-1925), had made a splash in 1920 by promoting his “Walker plan” for converting apartments into co-ops. Eight Walker buildings were converted that year, and the Northumberland, not a Walker building, rode the co-op bandwagon to conversion in October. At a time when the city was growing quickly and rents were climbing, the cooperative scheme was an attractive option for owners to control costs and invest in their homes.

Many of the enthusiastically-founded 1920s cooperatives failed during the Depression, unable to pay their underlying mortgages. Co-ops grew less common in Washington, although the Northumberland survived unscathed. In fact, employees at the Northumberland received raises, building improvements were made, and monthly stockholder assessments were temporarily dropped. Board minutes show that during World War II discussions were held about what to do if the Germans started bombing Washington.

After the war the neighborhood around the Northumberland began to decline. Embassies and wealthy property owners moved away, and real estate values dropped. Bucking the trend, the Northumberland gained a reputation as a haven for “old Washington,” with many long-time residents staying on. At one point in the 1960s the lobby was redecorated in a contemporary Danish modern style, as if to visually mark what may have seemed the twilight of the venerable building’s historic ambience. Then came the 1968 riots, with burning and looting less than two blocks away on 14th Street. According to Richard Cote, people were on the roof of the building during the riots, pouring water to protect it from flying cinders.

An original apartment room chandelier (photo by the author).

In the late 1970s, the downward trend finally began to reverse as the historic character of buildings like the Northumberland, along with their affordability, became a draw. The building earned landmark status in D.C. in 1978, and the exterior was listed on the National Register of Historic Places two years later, the same time that a thorough restoration of the lobby was undertaken. People were charmed by the many elements of the building that had never changed, such as the quaint mail delivery system. A 1978 Washington Post article noted that “Each day the postman presents the mail to Miss [Elsie H.] Anderson, the building’s resident manager. She places it in a wicker basket that has been used for that purpose for 40 years, and personally delivers the mail to each apartment.”

The Northumberland stands today as one of the oldest continuously operating cooperatives in the city. Cooperative ownership “has been a good thing,” says Patrick Sheary, president of the board. “It kept the building original inside and out rather than having a contractor gutting it and renovating it on the cheap. We own the building so we take care of it.” The Northumberland is well positioned for another hundred years of elegant urban living.

* * * * *

With reporting by Susan Decker in Mount Pleasant. Special thanks to Susan and to Richard Cote, Patrick Sheary, and other members of the board and residents of the Northumberland. Other sources included James Goode, Best Addresses (1988); the National Register of Historic Places nomination for the Northumberland (1980); the Northumberland Apartments website; and numerous newspaper articles.

Recent Stories

For many remote workers, a messy home is distracting.

You’re getting pulled into meetings, and your unread emails keep ticking up. But you can’t focus because pet hair tumbleweeds keep floating across the floor, your desk has a fine layer of dust and you keep your video off in meetings so no one sees the chaos behind you.

It’s no secret a dirty home is distracting and even adds stress to your life. And who has the energy to clean after work? That’s why it’s smart to enlist the help of professionals, like Well-Paid Maids.

Unlock Peace of Mind for Your Family! Join our FREE Estate Planning Webinar for Parents.

🗓️ Date: April 25, 2024

🕗 Time: 8:00 p.m.

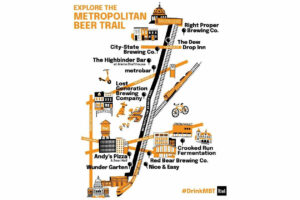

Metropolitan Beer Trail Passport

The Metropolitan Beer Trail free passport links 11 of Washington, DC’s most popular local craft breweries and bars. Starting on April 27 – December 31, 2024, Metropolitan Beer Trail passport holders will earn 100 points when checking in at the

DC Day of Archaeology Festival

The annual DC Day of Archaeology Festival gathers archaeologists from Washington, DC, Maryland, and Virginia together to talk about our local history and heritage. Talk to archaeologists in person and learn more about archaeological science and the past of our