Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

The story of S. Kann, Sons & Co., once Washington’s second largest department store behind Woodward & Lothrop, begins just north of us in Baltimore. There a German immigrant named Solomon Kann (1836-1908) opened a clothing store during the Civil War. As time went on, he brought his three sons—Louis Kann (1860-1920), Simon Kann (1861-1932), and Sigmund Kann (1865-1930)—into business with him. In the early 1890s, the family learned that a Washington, D.C., clothing merchant by the name of Dorsey Carter wanted to sell his business, and Solomon Kann sent Louis and Sigmund to investigate. The sons bought the stock of the old business and later two other nearby stores as well, combining their offerings and opening S. Kann, Sons on the northeast corner of 8th Street and Market Space NW in 1893. The location was perfect, right in the heart of Washington’s commercial district, directly across Pennsylvania Avenue from Center Market (where the National Archives now stands). Louis (called “short, quick, and aggressive” by the Washington Post) and Sigmund (“tall, deliberate, and reserved”) soon brought Simon (“short, stocky, and wearing thick-lensed spectacles”) in as well, and the brothers’ store prospered under their energetic management.

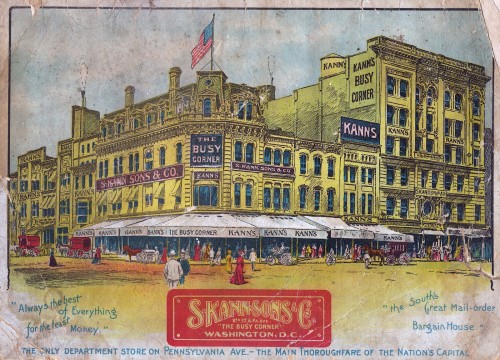

Kann’s Busy Corner in 1907 (author’s collection).

Kann’s, like Woodies which had preceded it by only a few years, was one of the new breed of progressive department stores, imbued with radical business policies: goods were offered at a single, fixed price—no haggling—and customers were welcome to return goods they didn’t want and have their money cheerfully refunded, something previously unheard of. Kann’s and Woodies both vigorously promoted the “customer-is-always-right” philosophy, and it paid off in booming sales, which allowed them to keep prices low. Kann’s in particular was committed to selling goods at the lowest price possible, even resorting to shaving prices to various fractions of a cent—two thirds, three quarters, seven eights—a tactic that had a powerful psychological effect on price-conscious shoppers. “Always the best of everything for the least money,” Kann’s advertised.

Kann’s circa 1935 (Source: Library of Congress).

Frances Folsom Cleveland (1864-1947), the stunningly attractive first lady who had returned to the White House with her husband in 1893 for his second term, was an early customer of Kann’s. According to the Washington Post, “Washington was eager to see and admire her as she drove about the streets in the highly polished White House landau, drawn by a fine team of horses, attended by a coach and footman, visiting many of the stores along the avenue.” The story goes that as she shopped at Kann’s she attempted to have her purchases charged to her account, just as she did everywhere else, only to be informed by the nervous clerk that Kann’s policy was strictly cash-and-carry. Fortunately, Mrs. Cleveland had sufficient funds to cover her purchases and took no offense. The bargains at Kann’s were worth it.

Continues after the jump.

Advertisement from The Washington Times, Sept. 30, 1897.

Kann’s, which advertised its location as “The Busy Corner,” gradually acquired or leased various adjoining buildings to steadily expand its complex. But eventually it ran up against the other large retailer on the block, A. Saks & Co., which occupied a prominent six-story building on the adjacent corner, constructed in 1885. Andrew Saks (1847-1912) had begun his dry goods business here in Washington and only later opened a store in New York, where his firm would become famous. The two businesses competed with each other directly as clothing retailers until 1901, when they reached a convenient agreement. Kann’s turned over all their men’s merchandise to Saks, and Saks gave all their women’s and children’s stuff to Kann’s. The arrangement kept the two stores going quite amicably but did nothing to resolve Kann’s craving for more room.

(Source: Author’s collection.)

In 1924 the company purchased the Homer Building at 13th and F Streets NW and a few years later the building next to it. Plans were announced in 1928 to build a new, larger store at this site to replace the cramped old warren of structures on Market Space, but the plan was never carried out. Instead, in 1932 Kann’s bought and absorbed the adjacent Saks store, allowing it to expand out into the entire southern end of the block. While the company retained ownership of the Homer Building on 13th Street, the store remained in its original location for another four decades.

Unlike many Washington commercial establishments, Kann’s generally did not discriminate against African American customers, although its record was not unblemished. In 1946, Kann’s management caved in to pressure from whites, who constituted 75 percent of its patrons, and agreed to jim-crow its lunch counter. A section at the far end of the counter was designated for non-white customers. Previously, Kann’s had been one of the few stores that didn’t have such a policy. The white customers had their way for four years, until Dr. Mary Church Terrell’s Co-ordinating Committee for the Enforcement of the D.C. Anti-discrimination Laws instituted a boycott of Kann’s in 1950. Kann’s soon reversed its ill-advised policy. In the end, Kann’s would be known as a remarkably liberal business; among other achievements, it was the first in Washington to use black mannequins in its display windows.

Kann’s Virginia Square store in 1953 (Photo by Lionel Freedman, courtesy © Lionel Freedman Archives via DC Public Library).

In 1951, Kann’s opened its only suburban branch store, in Arlington, Virginia, on an empty site west of Clarendon dubbed Virginia Square. As described in the Post, the store’s exterior, designed by the architectural firm of DeYoung Moscowitz & Rosenberg, was of “brick, crab orchard stone, glass and natural wood” intended to “harmonize the structure with the casual beauty of the Virginia environs.” The modernist building opened in November 1951 within weeks of the opening of rival Hecht Company’s “Parkington” branch store less than a mile away. The adjoining Virginia Square shopping center debuted the following year.

The Virginia Square store offered every efficiency a mid-century shopper could want, including parking for 1,000 cars and large, unobstructed shopping floors color-coded to indicate the type of merchandise on display. Items could be purchased one by one and dropped off at a collecting center on each floor that would send them down to the parking level via conveyor belt for speedy delivery to one’s car. On a more eccentric level, a large glassed-in cage on the second floor housed four squirrel monkeys, imported from Brazil, that were destined to leave a vivid impression on many a young Kann’s shopper. Downstairs in the basement was the store restaurant, called the “Kannteen.”

The main store downtown had for many years used nearby warehouses for storage, and, in a foretaste of future tragedy, these warehouses suffered significant damage in two major fires, in 1947 and 1953. After the second fire, which was set by a young warehouse employee upset with his supervisor, the District coincidentally decided to close a nearby fire department facility that housed a rescue squad. Kann’s officials pleaded with the city to keep the firehouse open and put fire-fighting equipment in it. A Kann’s attorney was quoted as saying “Our viewpoint is that one trained fireman at that station house is 100 times as valuable as the best equipment a few minutes away. This is an area of old buildings, and after the fire Saturday, we think it is particularly to our interest to have added protection.” District officials were unmoved, and the station was closed.

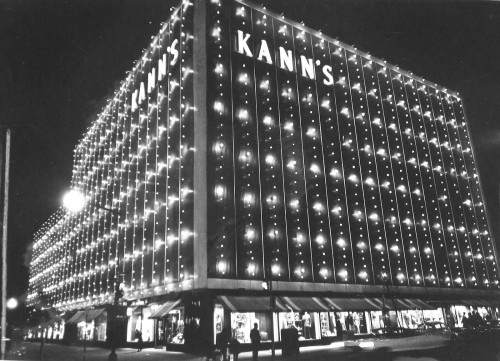

Kann’s then began the slow decline that permeated downtown businesses in this era. Kann’s officials decided in 1959 to try to boost the main store’s appeal by “modernizing” it, hiding its assortment of old buildings behind uniform, grey, anodized-aluminum sheeting. The result, duly approved by the Fine Arts Commission, was a giant featureless box that would ultimately doom the historic buildings hidden behind it. However modern and up-to-date it may have seemed when completed in 1961, the box’s appeal did not last long.

The remodeled Kann’s, decorated for Christmas, 1969. (Source: DC Public Library, Star Collection, © Washington Post)

In 1971 Kann’s was sold to a West Virginia company that kept it going for just four more years. The store finally went out of business in May 1975, much to the consternation of long-time customers and employees alike. The owners said that Metro construction had driven them out of business, but the newspapers reported that the store’s real problem was that it had failed to adapt to changing times. Rather than aggressively courting suburban shoppers as other stores had done, Kann’s clung to the patronage of its dwindling downtown clientele. Its demise was inevitable.

As early as 1964, when Kann’s was still in business, the President’s Council on Pennsylvania Avenue had recommended tearing down the building and everything else in a broad triangular area north of Pennsylvania Avenue to be replaced by an array of sterile-looking office blocks. The council’s plan was thankfully never implemented, and the following year the Department of the Interior designated this area as the Pennsylvania Avenue Historic Site, which provided some protection to the Kann’s building. A succeeding group, the President’s Temporary Commission on Pennsylvania Avenue, refined the official plans for the avenue. That commission’s successor, the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation, finally developed a revised plan that was approved by Congress in 1975. The revised plan noted that its predecessor had been criticized for “sterility and over-monumentality” but nevertheless retained the idea of leveling a large “superblock” of properties, including the Kann’s building, and replacing them with a new residential complex of townhouses, apartments, and shops. An open square was also to be created in the southern part of the Market Space area, which would be in keeping with the original L’Enfant plan for the city.

The former Kann’s store in 1978 (Source: DC Public Library, Star Collection, © Washington Post)

On a single day in January 1978, the PADC acquired two major landmarks: the Willard Hotel at 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue for $5 million and the Kann’s Building for $4.3 million. Whereas the Willard was to be preserved and restored, the Kann’s Building was to be torn down according to the approved PADC plan. However, in the fall of 1978 DC’s Joint Committee on Landmarks recommended that PADC not be permitted to demolish the historically-landmarked building. Committee members thought enough hadn’t been done to explore preservation of some or all of the buildings hidden behind the grey aluminum. The store was “an extremely handsome building before the façade was put up,” Nancy Taylor, a member of the committee and a staffer for the National Capital Planning Commission, was quoted as saying. PADC countered that the old building was structurally unsound, that stabilizing it would cost $2 million, and that it was unclear what remained of the original Victorian facades underneath the aluminum sheathing. Further, according to the Post, the PADC argued that tearing down the historic building would indicate progress in an area of downtown that showed few signs of an economic turnaround.

In January 1979, as it prepared to demolish the building, the PADC instructed its contractor to remove a portion of the aluminum covering to determine whether any of the old façades underneath were still intact enough to be removed and possibly reused on other new buildings nearby. As had been the case with the old Greyhound Terminal on New York Avenue, removing the metal covering revealed that the old façades were remarkably intact. Don’t Tear It Down, the predecessor of the D.C. Preservation League, became involved in efforts to convince PADC to save and restore the entire old complex of buildings. A developer proposed turning the old buildings into residential units—an idea that today would seem like a no-brainer for the distinctive and irreplaceable structures.

PADC dug in its heels, saying it had to stick to its congressionally approved plan to tear down Kann’s and build the planned superblock of new buildings. At the request of Congress, the U.S. General Accounting Office reviewed PADC’s plans and actions and found that there was nothing improper or illegal about them.

On the scene after the fire was extinguished (Source: Archives of the D.C. Preservation League).

Then on March 31, 1979, the same day that the GAO issued its findings, the Kann’s building was consumed in a massive five-alarm fire, reported to be the worst to hit downtown D.C. in thirty years. The newspapers printed photos the next day of thick, acrid smoke billowing out of the doomed structure. The conflagration was reported at 2 o’clock in the morning and continued to burn until 2:30 in the afternoon. At the peak of their efforts, 150 firemen poured 1 million gallons of water per hour on the building to try to control the blaze. They were hampered by the fact that the building’s sprinkler system had been turned off and partially disassembled (the fire department had previously recommended that PADC keep it functional) and by the impenetrable aluminum cocoon that prevented access to much of the building.

The ruins after demolition had begun, 8th Street corner (Source: Historic American Buildings Survey).

Crews spent two hours in the early morning removing six of the aluminum panels on 7th Street with power saws and air chisels. Later a wrecking crane was used to dent some of the panels on 8th Street so that firemen could pull them off. Even after the blaze was put out, firemen kept up a watch throughout the night to ensure that it did not start back up.

The ruins after demolition had begun, seen from 7th Street (Source: Historic American Buildings Survey).

“Although the roof collapsed and the inside of the building was virtually destroyed, there appeared to be little damage to the store’s elaborate 19th century façade,” the Post reported. Nevertheless, the Interior Department delisted the building as an historic landmark, and the PADC moved swiftly to demolish it as soon as the fire department had completed its investigation in April. None of the historic façade elements were saved, despite the PADC’s reported statements before the fire that it would consider doing so. The D.C. fire marshal testified at a Senate hearing in May that the fire was of suspicious origin and may have been started by someone inside the building. “The possibility of an accidental cause of fire is excluded,” he said. Although there was no evidence that the PADC had any involvement in setting the fire, its exact cause was never determined.

Demolition nears completion. (Source: DC Public Library, Star Collection, © Washington Post)

The Kann’s site remained empty for another decade, until the Market Square complex, designed by Hartman Cox, was completed in 1991. The PADC had changed its plans and done away with the superblock idea. The twin Market Square buildings, which Benjamin Forgey has called “stentorian landmarks,” are consciously (or perhaps self-consciously) designed to contribute to a grand, ceremonial Pennsylvania Avenue, in contrast to the hurly-burly of the Victorian buildings that used to be there. Meanwhile, the Kann’s Virginia Square store was taken over by George Mason University Law School in 1979 and has been occupied by the university ever since. Plans are to demolish that building too, however, so that eventually no trace of Kann’s will survive.

The eastern Market Square building now stands on the former Kann’s site (photo by the author).

Special thanks to Faye Haskins of the Washingtoniana Division of the D.C. Public Library and to Jo-Ann Neuhaus for their invaluable assistance. The views expressed in this article are my own.

Recent Stories

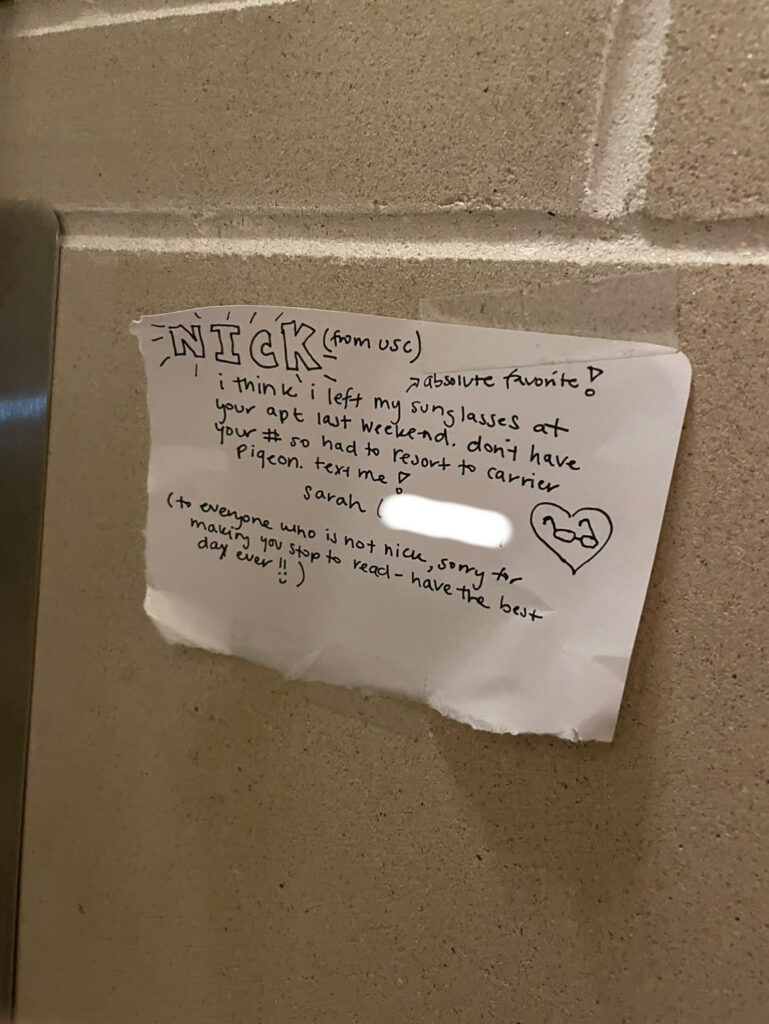

Thanks to Alex for sending from Adams Morgan. Nick, if you have Sarah’s sunglasses – email me at [email protected]

Unlike our competitors, Well-Paid Maids doesn’t clean your home with harsh chemicals. Instead, we handpick cleaning products rated “safest” by the Environmental Working Group, the leading rating organization regarding product safety.

The reason is threefold.

First, using safe cleaning products ensures toxic chemicals won’t leak into waterways or harm wildlife if disposed of improperly.

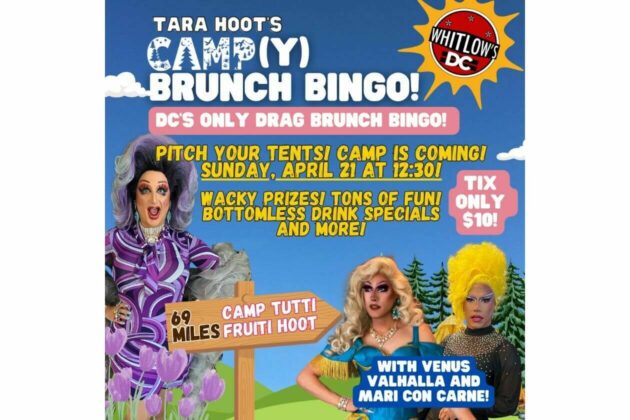

Looking for something campy, ridiculous and totally fun!? Then pitch your tents and grab your pokers and come to DC’s ONLY Drag Brunch Bingo hosted by Tara Hoot at Whitlow’s! Tickets are only $10 and you can add bottomless drinks and tasty entrees. This month we’re featuring performances by the amazing Venus Valhalla and Mari Con Carne!

Get your tickets and come celebrate the fact that the rapture didn’t happen during the eclipse, darlings! We can’t wait to see you on Sunday, April 21 at 12:30!

DC Labor History Walking Tour

Come explore DC’s rich labor history with the Metro DC Democratic Socialists of America and the Labor Heritage Foundation. The free DC Labor History Walking Tour tour will visit several landmarks and pay tribute to the past and ongoing struggle

Frank’s Favorites

Come celebrate and bid farewell to Frank Albinder in his final concert as Music Director of the Washington Men’s Camerata featuring a special program of his most cherished pieces for men’s chorus with works by Ron Jeffers, Peter Schickele, Amy