Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Mark Twain is said to have called it the ugliest building in America, a sentiment later echoed by President Harry S Truman, who thought it the country’s “greatest monstrosity.” Now, to tear down this monstrosity would be unthinkable. Declared a national historic landmark in 1971, the massive block-long Eisenhower Executive Office Building, as it is now called, is widely cherished as a stunningly exuberant relic from a bygone era that could never be replicated. Whatever has been thought of it across the years, the building achieves architecture’s highest calling, impressing its unique identity relentlessly upon all who witness it and demanding a response.

(Author’s collection.)

As long as the federal government has been in Washington, cabinet department office buildings have stood on this site and the corresponding space on the other side of the President’s House. George Washington wanted them here, and under his direction, architect George Hadfield (1763-1826), designed the first two distinguished, federal-style buildings, which were ready for early bureaucrats to occupy when the government moved to Washington in 1800. After the British burned the buildings in 1814, they were reconstructed, and two more matching buildings were added, one on either side, to form a neat and symmetrical Executive Branch campus surrounding the President’s House. On the east side, along 15th Street, stood the State Department to the north and the Treasury Department to the south. To the west, along 17th Street, were the Navy and War Departments. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

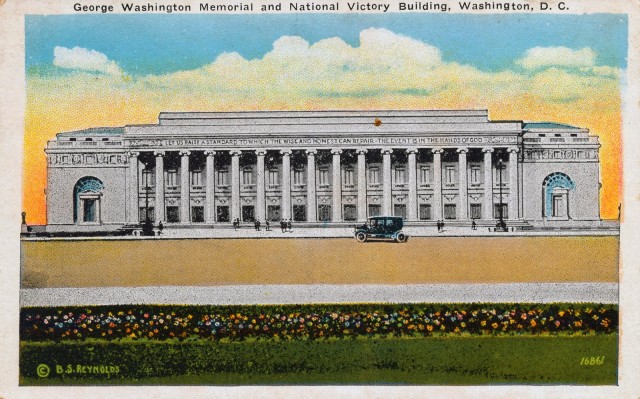

Around the turn of the last century city planners and others worried that the nation’s capital did not have a suitably grand and dignified meeting hall where large assemblies and conventions could gather and celebrate the greatness of America. A spacious 6,000-seat convention hall had been built in Mount Vernon Square in 1875 (see our previous profile), but it was in the old red-brick Victorian style and too far removed from the Mall to satisfy the aspirations of the Beaux Arts generation. The new imperial, white-marble Washington, as envisioned by the McMillan Commission, needed a massive and powerful-looking auditorium with a forest of imposing classical columns lining its facade. At least Susan Whitney Dimock (1845-1939), a New York socialite, certainly thought so, and she made it her life’s work to have such a meeting hall built. But despite endorsements from several presidents and countless other powerful people, the hall was never meant to be.

Postcard of the planned memorial from the 1920s (author’s collection).

Dimock was born to the wealthy Whitney family of New York, the daughter of James Scollay Whitney (1811-1878). Two of her brothers became successful and powerful industrialists in an age of industrialists. She married Henry F. Dimock (1842-1911), a New York attorney who also became a prominent businessman, working in large part with Whitney family interests. Susan clearly wished to leave her own mark for the betterment of the country, and she set her sights on a memorial to George Washington—never mind that one already had been completed in 1884. Read More

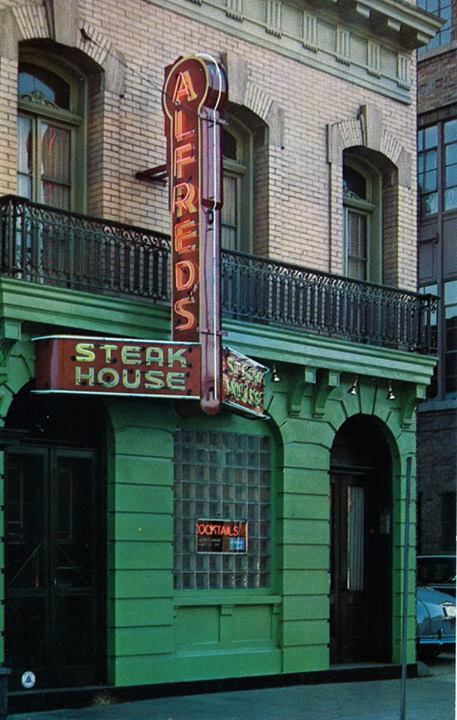

Not a proper Streets of Washington like the awesome one from earlier this week but this photo from the collection of John DeFerrari is so freaking cool. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats

I had no idea that:

“The storefront at 1610 U Street NW supposedly housed a speakeasy in Prohibition days. In the 1940s and 1950s it was Alfred’s Steak House, prominently located at the western end of the “Black Broadway” of U Street. According to Stetson’s web site, Alfred’s customers included Duke Ellington, Pearl Bailey, Nat King Cole, Count Basle, and Sarah Vaughn. Stetson’s Bar and Grill opened on the site in 1980.”

I also had no idea that Stetson’s has been open since 1980!?!…

1610 U Street, NW today

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

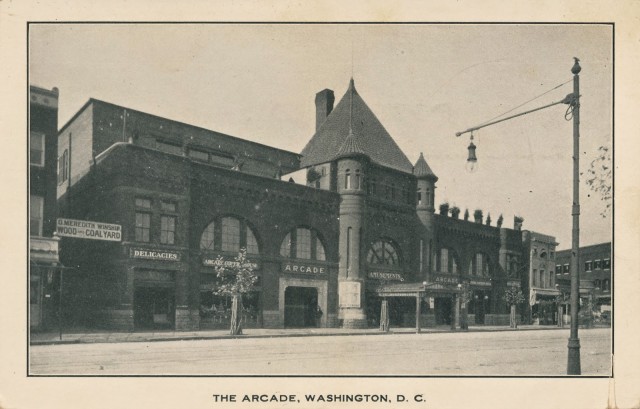

Fourteenth Street NW between Irving Street and Park Road, the commercial hub of Columbia Heights, bustles with activity today. Though it took decades for the block to bounce back from the devastation of the 1968 riots, its new vitality is not really new. One hundred years ago, this block had the same central role in the life of upper Northwest, and the Arcade, a massive multi-purpose entertainment and commercial complex located where the DC USA mall now stands, was its heart.

(Author’s collection).

The Arcade began as a Capitol Traction Company streetcar garage, a spacious structure built in 1892, when streetcar lines were first being electrified and extended past the old city limits (at Florida Avenue) into the hilly countryside of upper Northwest. The building’s fanciful Romanesque Revival style, complete with arched windows and turreted corners, was in vogue at the time and was similar to that of the Metropolitan Railway car barn, completed in 1896, which still stands today as a condominium complex at 1400 East Capital Street NE.

The Park Road garage served as the terminus of the 14th Street trolley line for only about a decade. In 1906, 14th Street was extended north to Decatur Street, and streetcar tracks were quickly laid on the newly graded and paved thoroughfare. A large and attractive new car barn was built at the Decatur Street terminus (it also still stands today), rendering the old Park Road structure obsolete. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

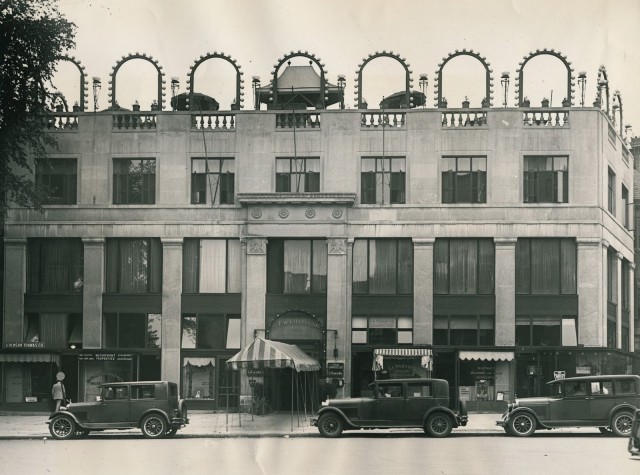

Running a fashionable supper club in the 1920s was not for the fainthearted. Certainly there was plenty of money to be made, and club owners outdid themselves to create the most exotic destinations imaginable. But these were the days of Prohibition, and the “dry” agents were always on the look-out for places where people seemed to be having a little too much fun. One such place was Le Paradis, one of the DC’s ritziest 1920s nightspots, located at 1 Thomas Circle NW.

The Le Paradis at 1 Thomas Circle, with its rooftop garden, in 1931 (Author’s collection).

Le Paradis was the creation of legendary impresario and bandleader Meyer Davis (1893-1976), who was born in nearby Ellicott City, Maryland, and moved to the District as a child with his family. Davis loved music from an early age, starting his own five-member band (which played for $25 an evening), after his high-school orchestra rejected him. In 1914, while he was a law student at George Washington University, his band was breaking new ground playing music for hot new dances like the bunny hug, the turkey trot, and the grizzly bear. Soon his group had a gig playing lunches and dinners at the Willard Hotel, and Davis quickly settled on the supper club scene as his preferred métier. Tall, slim, and balding, Davis had an urbane air that appealed to his wealthy clientele, and his energy and verve in twirling his conductor’s baton seemed to always bring the audience to their feet. In later years, he would be dubbed the “Toscanini of society band leaders.” Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

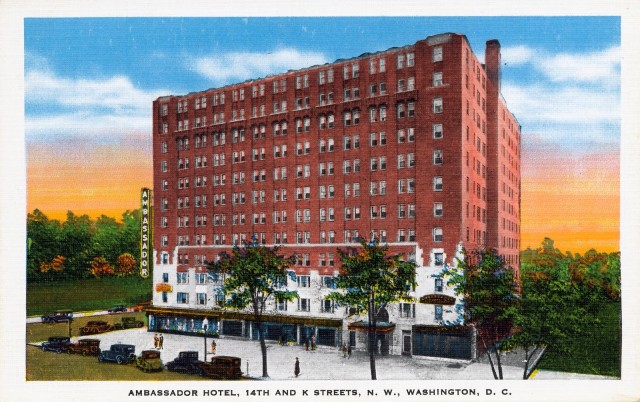

The Ambassador Hotel, located on the southwest corner of 14th and K Streets NW across from Franklin Square, was a showcase of modern amenities and conveniences when it opened in September 1929. It was the work of successful developer Morris Cafritz (1890-1964), who lived at the hotel for a number of years and had his offices there. An important and distinctive DC landmark, the Ambassador nevertheless didn’t aim for the heights of refinement and elegance embodied in, say, the Willard or the Mayflower. Instead it was designed for the common man, advertising itself as the “stopping place of experienced travelers.”

An early postcard view of the Ambassador. Adjoining buildings are not shown. (Author’s collection).

Born in Russia, Cafritz arrived in the U.S. as a child. His father eked out a living running a small neighborhood grocery store off of North Capitol Street. As a young man, Cafritz tried his hand at a variety of early businesses—he ran a coal company, then a saloon on 8th Street SE. He set up chairs in an empty lot and showed silent movies. He opened a bowling alley in the old Center Market, then added several more, until they called him Washington’s Bowling King. Like many businessmen of his era, his early retail successes led him to move into real estate, and it was as a speculative developer that he had his greatest success. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

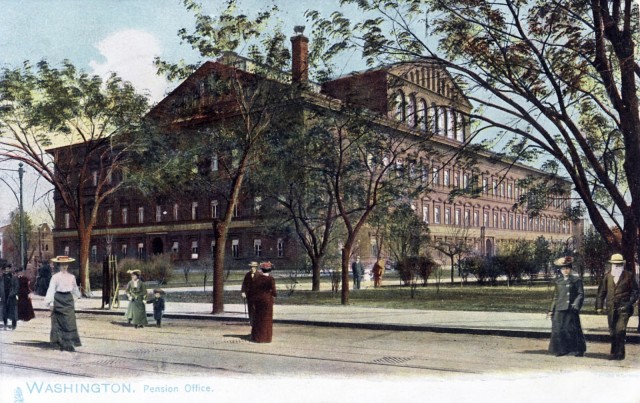

Just east of the hustle and bustle of Chinatown and the Verizon Center stands a great Italian Renaissance Revival pile of pressed red brick known as the Pension Building, home to the National Building Museum. The building is one of the city’s best venues for large events and has hosted inaugural balls for presidents going back to Grover Cleveland’s in 1885, before it was even finished. It’s dramatic, historic, and treasured now, but like many architectural landmarks it is ultimately a rather odd building, and it’s certainly had more than its share of detractors over its lifetime.

The Pension Building today (photo by the author).

The Pension Building as it appeared in the early 1900s (author’s collection).

The building was the brainchild of Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs (1816-1892). By 1881, the brilliant, vainglorious, 65-year-old Meigs was rounding out a remarkable career of engineering accomplishments. Meigs was a man of exceptional drive, intellect, irascibility, and arrogance, who had been fascinated by engineering from an early age. When he was just six years old, his mother described him as “high-tempered, unyielding, tyrannical toward his brothers, and very persevering in pursuit of anything he wishes.” As a young man he designed Washington’s first effective water supply system, a complex reservoir and aqueduct complex that included the magnificent Cabin John Bridge in Maryland—the longest single-span masonry bridge at the time—as well as the graceful Georgetown aqueduct bridge over Rock Creek. He went on to become supervising engineer for the expansion of the U.S. Capitol, where he worked, often contentiously, with architect Thomas U. Walter to create the lavish, elegantly decorated building we know today. An accomplished logistician, he served during the Civil War as Quartermaster General of the Army and is perhaps best known as the man who decided to build a cemetery around Robert E. Lee’s mansion in Arlington so that it would never be usable again as a home. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

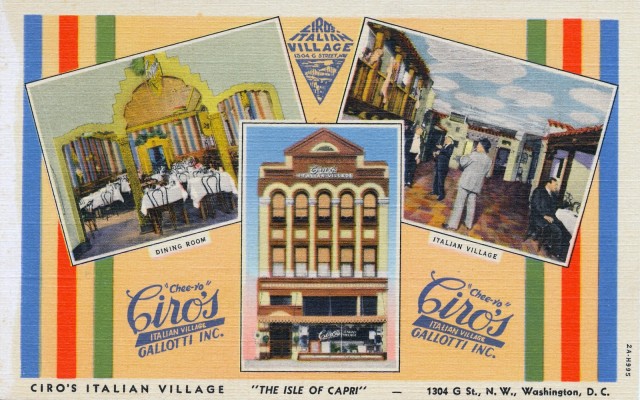

The recent closing of Famous Luigi’s after 70 years in business at 1132 19th Street NW brings to mind fond recollections of the many old-style Italian restaurants known as “red sauce joints” that used to offer Washingtonians pizza, pasta, and warm-hearted service in great abundance. DC has been home to Italian restaurants since at least the 1870s, but a handful from the first half of the 20th century stand out as pioneers. One of those was the place where Luigi Tito Calvi (1889-1963), the founder of Famous Luigi’s, got his start. It was Ciro’s Italian Village, at 1304 G Street NW downtown.

Circa 1932 postcard from Ciro’s Italian Village (author’s collection).

Ciro’s was creation of Ciro (pronounced “Cheero”) Gallotti (1883-1948), a feisty immigrant from Naples who had a lasting impact on the Italian restaurant scene in DC. Gallotti was an effusively outgoing individual (“one high-strung and ever exciting chum,” according to the Washington Post) who was well-suited to the role of restaurateur. He began not in the restaurant business but as a musician, a french horn player for the Italian Navy Band, according to a family history prepared by his nephew Marty Gallotti (1927-2013). Ciro loved music and played the horn since he was a boy. With his future wife Guilia, he emigrated to the U.S. in 1911, and the couple were married in New York City, where he got his first job with the Victor Herbert Orchestra before moving to Washington to live at the fashionable Raleigh Hotel (previously profiled here).

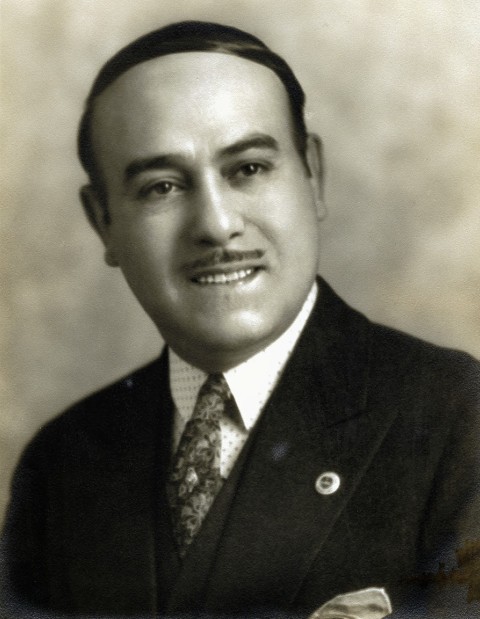

Undated photo of Ciro Gallotti (courtesy of Peggy Coyle).

In Washington, Gallotti played in the orchestra at the popular Knickerbocker Theater at 18th Street and Columbia Road NW in Adams Morgan. On January 28, 1922, a massive snowstorm dumped two feet of snow on DC roads and brought traffic to a standstill. As Gallotti tried to get to work that evening, he got stuck on 16th Street and decided he had no choice but to turn back home. That same night the Knickerbocker suffered one of the greatest disasters in the city’s history when the huge snowfall caused its roof to collapse onto a full house of moviegoers. Many of Gallotti’s fellow musicians were injured, and a few died. Gallotti took this as a sign that he should get out of the music business, and in October of that same year he opened his first restaurant, Gallotti’s Italian-American Restaurant, across the street from the Raleigh on Pennsylvania Avenue.

1201 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in 1919. Gallotti’s first restaurant would open here 3 years later (Source: Library of Congress).

We’ve previously profiled the little two-story building where he rented space, a shop that hosted many businesses over the years. Modestly advertising his new eatery as “a good place to eat where prices are moderate,” Gallotti struggled at first. For the first two years, in summer months Guilia would supplement the family’s income by running a concession stand in North Beach, Maryland. But Gallotti’s eventually caught on, and Ciro stayed in business at this location for at least 6 years. Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, to be published this September by the History Press, Inc. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Though it receives little attention in the media, competitive canoeing ranks high among the city’s sports achievements. Washington has participated in competitive flatwater canoeing at the Olympics ever since the sport was first introduced in 1924, and much of America’s success has been due to the athletes of the venerable Washington Canoe Club, headquartered in one of the Georgetown waterfront’s most historic and picturesque structures, a 1905 boathouse at 3700 Water Street NW. The green wooden-shingled structure, perched on the edge of the flood-prone Potomac river, has deteriorated over the years and gradually fallen into disrepair. Its future is now largely in the hands of the National Park Service.

Washington Canoe Club (photo by the author).

A hundred years ago, the Potomac river was the center of attention for summer sports and recreation, a place where refreshing breezes off the water could ease the swelter of un-air-conditioned city living. Many people would set up summer camps along either side of the Potomac from Georgetown to Great Falls and beyond, and hundreds would line the shores of the river or the railings of the Aqueduct Bridge to watch hotly-contested boat races. A June 1904 article in The Washington Post rhapsodized that “The beautiful stretch of water from the Analostan [Theodore Roosevelt Island] Boat House up to within a dozen furlongs of the Chain Bridge is the one most utilized by the oarsmen and canoeists, and the ever-passing throng makes the stream take on the appearance of the Grand Canal at Venice, with the gondolas left out.” Read More

Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, to be published this September by the History Press, Inc. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

The early 20th century was in many ways a golden era for casual restaurants. The rules of the business were changing rapidly, and those who could tell which way the wind was blowing had the opportunity for tremendous success. Lunchrooms had been proliferating since the 1890s, offering fast, inexpensive meals to working folk who could no longer easily go home for lunch and who didn’t feel comfortable patronizing saloons. Then Prohibition killed off the saloons altogether, and the demand only increased for simple, homestyle cooking served quickly and inexpensively. Cafeterias were one solution. The first American eatery to be called a cafeteria had opened in 1893 at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and it was an instant hit. As cafeterias gained in popularity over the coming decades, they nearly always sold the same basic, no-frills “comfort” fare—breakfast dishes, sandwiches, meatloaf, salads, cakes, pies, and the like.

Postcard from 1932 (Author’s collection).

Perhaps the best known in Washington was Sholl’s Cafeteria and Dining Room, opened by Evan A. Sholl (1899-1983) in 1928 at Connecticut Avenue and L Street NW. Sholl, the second-youngest of 13 children born to a Pottsville, Pennsylvania farmer, had started out in life with little to his name. He earned a hardscrabble living at an assortment of odd jobs—busboy, window washer, shoe factory hand—just as J. W. Marriott was doing at about the same time. At age 20 he opened his first restaurant, which quickly bankrupted him. After that he went to work for the Kresge retail chain, which transferred him to its Washington store at 7th and E Streets NW in 1927. He regained his financial footing there and, with more experience under his belt, set out on his own again with Sholl’s Cafeteria. This time it worked. Read More