Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

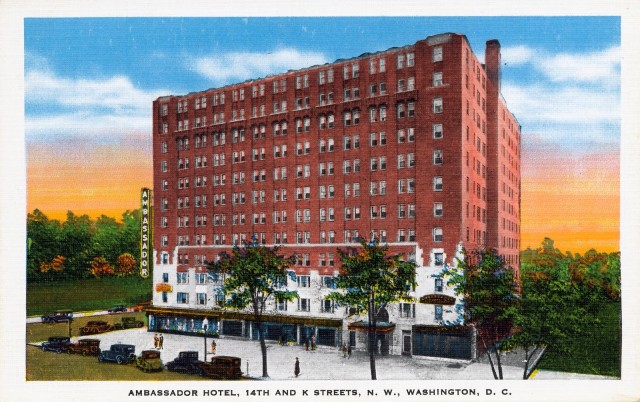

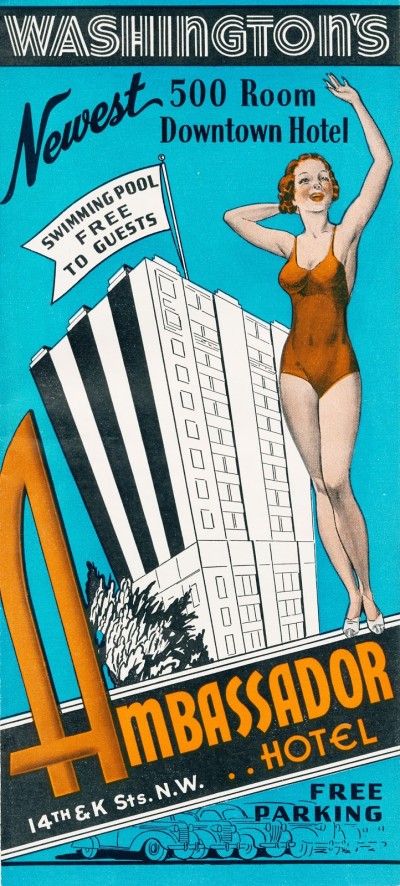

The Ambassador Hotel, located on the southwest corner of 14th and K Streets NW across from Franklin Square, was a showcase of modern amenities and conveniences when it opened in September 1929. It was the work of successful developer Morris Cafritz (1890-1964), who lived at the hotel for a number of years and had his offices there. An important and distinctive DC landmark, the Ambassador nevertheless didn’t aim for the heights of refinement and elegance embodied in, say, the Willard or the Mayflower. Instead it was designed for the common man, advertising itself as the “stopping place of experienced travelers.”

An early postcard view of the Ambassador. Adjoining buildings are not shown. (Author’s collection).

Born in Russia, Cafritz arrived in the U.S. as a child. His father eked out a living running a small neighborhood grocery store off of North Capitol Street. As a young man, Cafritz tried his hand at a variety of early businesses—he ran a coal company, then a saloon on 8th Street SE. He set up chairs in an empty lot and showed silent movies. He opened a bowling alley in the old Center Market, then added several more, until they called him Washington’s Bowling King. Like many businessmen of his era, his early retail successes led him to move into real estate, and it was as a speculative developer that he had his greatest success.

Cafritz began building quality, affordable rowhouses in the 1910s in the Park View neighborhood near Soldiers’ Home. His big move came in 1922, when he purchased most of the old Columbia Golf Club north of Petworth and began constructing houses on the land—the equivalent of 90 city blocks—on which he built more than three thousand homes. His solidly built houses sold well in a rapidly expanding city. After that, Cafritz began building large apartment houses at prime locations throughout the city, vying with Harry Wardman for the biggest and best opportunities. Cafritz apartment buildings included the Majestic and Hightowers on 16th Street among many others.

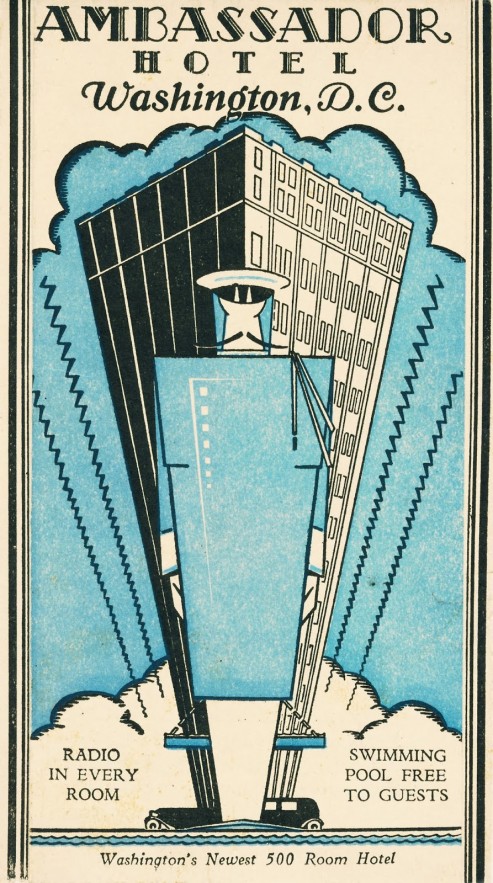

An early brochure from the hotel – click to enlarge (Author’s collection).

Cafritz was really beginning to hit his stride when he announced plans in 1928 for a $3 million 500-room hotel at 14th and K Streets NW, where he previously kept his offices. The new hostelry would include amenities such as a swimming pool, gym, and roof garden. Eight stores were slated to open at street level. Most significantly, according to the Washington Post, the trendy new hotel was to be “the first hotel in Washington equipped with a radio loud speaker in every room and one of the first hostelries in the country in which radio will be part of the customary service without extra charge.” Guests enjoyed the luxury of choosing between two different radio stations (WRC and WMAL) “by the mere turning of a switch.”

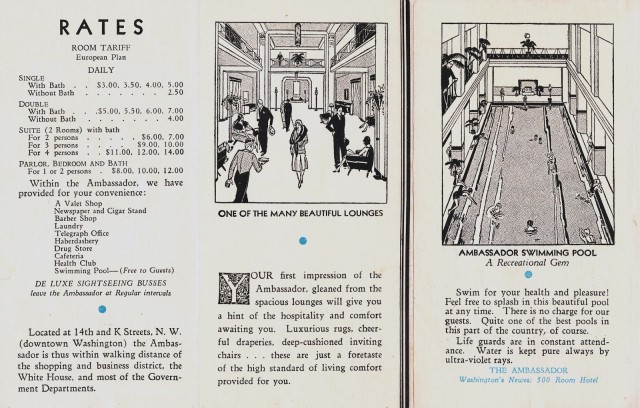

A 1936 postcard view of the Ambassador (Author’s collection)

Designed by D.C. architect Harvey H. Warwick (1893-1972) and completed in 1929, the new hotel was faced in burnt-orange pressed brick with Indiana limestone trim. Regarding style, the Washington Post explained that “in keeping with the trend of the times, the modern was decided upon as the keynote to influence architecture as well as interior decoration.” In fact the building was an eclectic mix of motifs, ranging from Gothic Revival balconies around the 11th story to Art Deco detailing at the roofline. At street level, “a beautiful two-story arched entrance with quaintly carved woodwork, modernistic hanging lamp and ornamental bracket lamps afford a most inviting approach,” according to the Post.

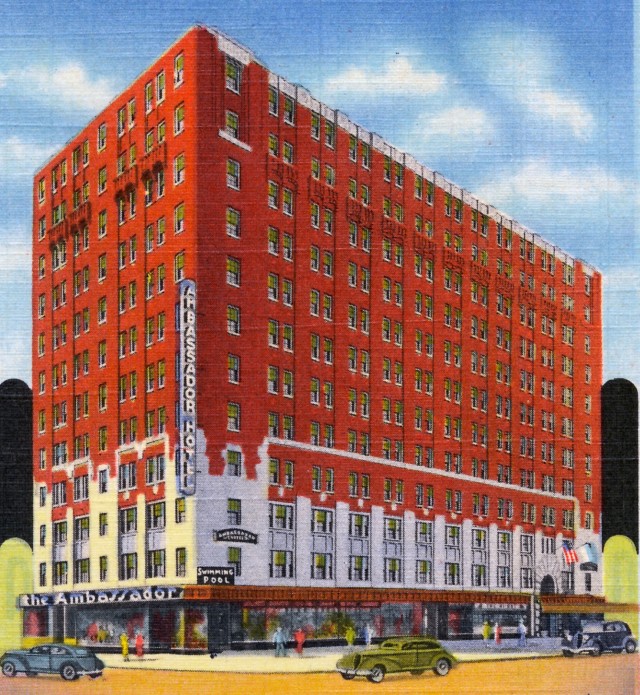

Brochure from the 1930s (Author’s collection).

Guest rooms were outfitted with custom-designed wallpaper as well as “modernistic carpets and draperies in rich color harmonies.” Walnut furniture, also “modernistic” in design, was accompanied by electric fans (no air conditioning yet) and floor lamps. And, of course, there was the free radio service as well.

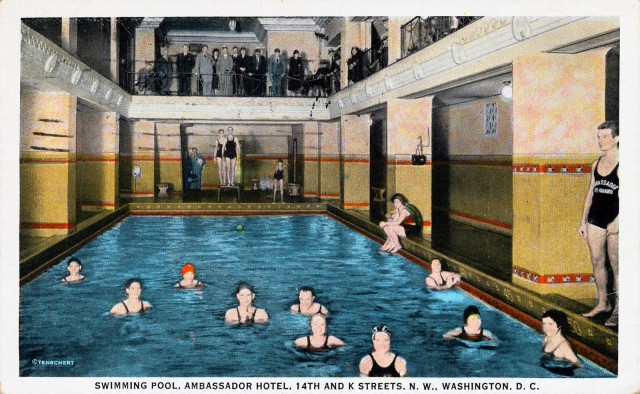

(Author’s collection).

The pool in the basement, said to be the first indoor pool in a D.C. hotel, featured decorative colored tile trim and was lit from within by submerged marine lights. The water was purified by a state-of-the-art ultraviolet radiation system that meant no chlorine or other irritating chemicals were needed. Refreshments were served at tables along a balcony overlooking the pool, where visitors could watch the bathers. An elaborate health club was fitted out in adjoining rooms, as much for the use of Cafritz himself, who loved to work out, as for the guests.

Gwendolyn Cafritz at her Foxhall Road home (Source: Library of Congress).

Cafritz moved in to the hotel with his new wife soon after it opened, taking up residence in a stylishly furnished suite on the top floor. Cafritz, at 41 a confirmed bachelor, had met and fallen in love with 19-year-old Gwendolyn Detre de Surany (1910-1988), an Hungarian ex-pat. Cafritz had actually first proposed to Gwendolyn’s mother, who turned him down but offered her daughter in her place. Cafritz fell genuinely in love with the young girl, who, as his wife, would in later years become a major figure in Washington society. The suite at the Ambassador was comfortable but not up to Gwendolyn’s aspirations for elegance, and finally in 1938, the couple and their sons moved to a luxurious new white Art Moderne mansion that Cafritz had built for them out at 2301 Foxhall Road NW. (The Cafritz mansion still stands, serving today as the home of the Field School.)

(Author’s collection).

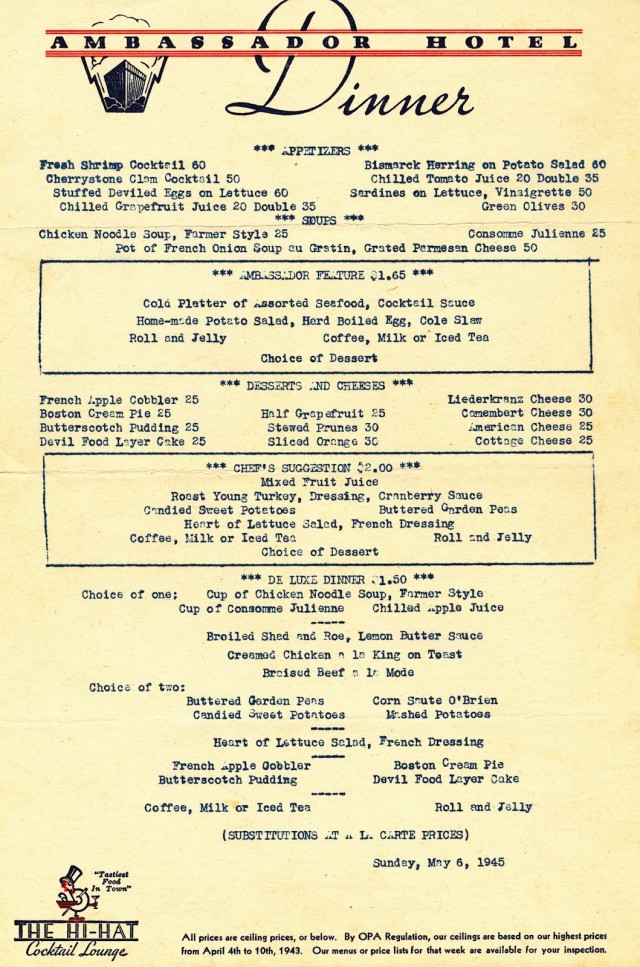

In March 1934, the Hi-Hat, a “smart new continental Cocktail Lounge and Cafe, styled in the modern manner,” opened on the top floor of the Ambassador. The Post raved about its decorations: “The silvery iridescence of kapiz shell gives the mellow effect of moonlight on the water, and the imported blue and white mirrors trimmed in stainless steel surrounding the columns introduces a new note in modern interior decoration.” The Hi-Hat Lounge quickly became a popular nightspot, offering top names in the nightclub circuit. Its opening act was Princess Harriet Purdy, a Hawaiian who strummed a ukulele while crooning languorous songs in her native tongue. For its one-year anniversary in 1935, the Hi-Hat offered a lavish “Maestros on Parade” show, featuring a throng of leading musicians from local theaters, nightclubs, and hotels performing en suite, with much dancing and “souvenirs and favors” distributed to the guests.

Ambassador dinner menu from May 6, 1945 – click to enlarge (Author’s collection)

The Hi-Hat probably reached its peak of popularity during World War II, when as a moderately-priced nightspot it became a favorite rendezvous for the many servicemen and women who passed through the city. An unusual attraction was the Julliard-School-trained Diana Thompson, as beautiful as she was talented, who sang and played jazz on her harp at the Hi-Hat in June 1945. The Evening Star reported that one sailor drinking at the bar, gazed at her and gulped, “How many of these things have I had?”

Undated postcards from the Ambassador (Author’s collection).

After the war, nightlife on 14th Street began to change. Sophisticated entertainment vanished, as did newspaper coverage of hotel nightclub acts. By the end of the decade the Hi-Hat was still popular, but it was a different sort of place. According to Washington Confidential, a sleazy tell-all potboiler from 1951, the lounge had become

“a gay drinking spot, much patronized by the lonesome of either sex because of its informality. When we asked a cab-driver where we could meet a “friend” he directed us to the Ambassador. We sat there five minutes, not long enough to attract a waiter’s eye. But the eyes of two blonde things, young and not bad-looking, were quicker. One asked us to buy her a drink. We did.

Before long we were old friends. They told us they’d spend the evening with us for $20 each. We said we had to catch a train. They thought we meant the price was too high and reduced it to $10—”if we had a place to take them.”

The old downtown, once the center of the city’s nightlife, entered a long period of decline, like other downtown areas in major U.S. cities. The stretch of 14th Street just outside the Ambassador became notorious for its prostitutes, peep shows, and strip joints. Just a block to the south, Benny’s Home of the Porno Stars jockeyed with This Is It? and the massive Casino Royal (itself once a distinguished supper club) for the sleaze trade. Running a respectable hotel in the area became a formidable challenge, although budget-minded customers could still be found.

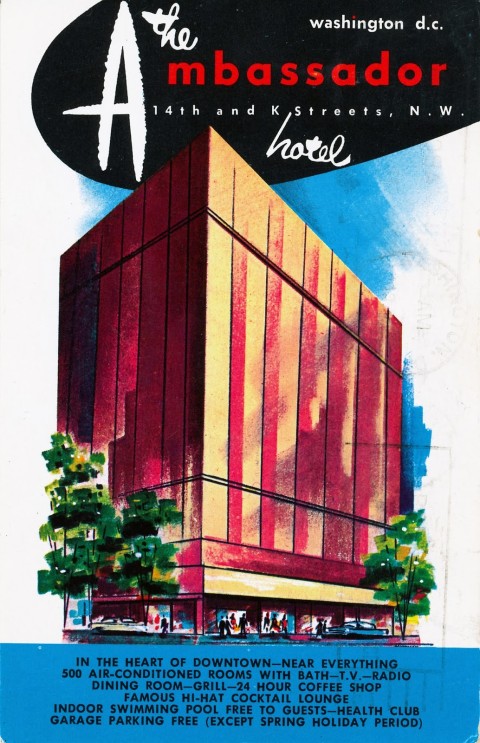

Brochure from 1966 – click to enlarge (Author’s collection).

Cafritz died suddenly of a heart attack in 1964, and a foundation was established that had control of the old hotel, among other assets. In 1972 the Cafritz Foundation leased the Ambassador to Ohio hotelier Drew Dimond, who hoped to refurbish it as a “simple hotel, plain and clean.” He hired off-duty military policemen to help keep the hookers out and planned to have the place thoroughly refurbished in time for the Bicentennial in 1976. It didn’t work out; Dimond had to give up when he couldn’t get financing for the renovations. In 1975. Sam Wong, a Chinatown restaurateur who operated the Moon Gate restaurant on the first floor, bought the hotel with the intent of undertaking repairs, but he soon also realized the project was infeasible, and the hotel finally closed for good in 1978.

The Ambassador Hotel site as it appears today (photo by the author).

But by the end of the 1970s the derelict neighborhood around Franklin Square was finally beginning to change again, as redevelopment began to move eastward from the crowded K Street corridor west of 16th Street. In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association, needing a new headquarters, purchased and razed the Ambassador, replacing it with a new cube-like office building that was completed in 1982. Soon the K Street office corridor extended all the way east to Mount Vernon Square, and the famous old hotels and nightspots of a previous era (with a few exceptions, such as the Hamilton Hotel) were just distant memories.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included Jack Lait and Lee Mortimer, Washington Confidential: The Lowdown on The Big Town (1951); Burt Solomon, The Washington Century: Three Families and the Shaping of the Nation’s Capital (2004), and numerous newspaper articles.

Recent Stories

For many remote workers, a messy home is distracting.

You’re getting pulled into meetings, and your unread emails keep ticking up. But you can’t focus because pet hair tumbleweeds keep floating across the floor, your desk has a fine layer of dust and you keep your video off in meetings so no one sees the chaos behind you.

It’s no secret a dirty home is distracting and even adds stress to your life. And who has the energy to clean after work? That’s why it’s smart to enlist the help of professionals, like Well-Paid Maids.

Unlock Peace of Mind for Your Family! Join our FREE Estate Planning Webinar for Parents.

🗓️ Date: April 25, 2024

🕗 Time: 8:00 p.m.

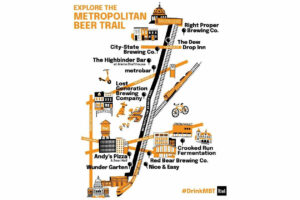

Metropolitan Beer Trail Passport

The Metropolitan Beer Trail free passport links 11 of Washington, DC’s most popular local craft breweries and bars. Starting on April 27 – December 31, 2024, Metropolitan Beer Trail passport holders will earn 100 points when checking in at the

DC Day of Archaeology Festival

The annual DC Day of Archaeology Festival gathers archaeologists from Washington, DC, Maryland, and Virginia together to talk about our local history and heritage. Talk to archaeologists in person and learn more about archaeological science and the past of our