Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

“Why is peace such an untellable tale?” wonders one of the patrons in a Berlin library as he is observed by a kindly angel in Wim Wenders’ classic film, Wings of Desire (1987). Just as peace is hard to write about, so it seems to be hard to erect a memorial to. We have countless monuments to wars and their heroes, but relatively few to celebrate peace. Even our Peace Monument, erected in 1877 at the foot of Capitol Hill where Pennsylvania Avenue ends, is really more about war than peace, and like the city’s many war memorials, people have bickered over it at least as much as they’ve celebrated its theme of tranquility.

The Peace Monument (photo by the author).

The monument was the brainchild of Admiral David D. Porter (1813-1891), one of the top two naval commanders of the Civil War. In 1864 Porter had led the successful naval campaign to take Fort Fisher at Wilmington, North Carolina, in what would be the last major naval campaign of the war. It was after the fall of Fort Fisher that Porter began a campaign to have a memorial erected to all of the brave Navy men who had been killed in the war, just as his famous father, War of 1812 hero David Porter (1780-1843), had commissioned the first naval monument to heroes of the Barbary Wars. That memorial, now known as the Tripoli Monument, had been completed in 1806 and originally stood in the Navy Yard but was moved to the Naval Academy in Annapolis in 1860.

When the Civil War ended, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles (1802-1878) made Porter superintendent of the Naval Academy, where he would go on to institute many reforms that enhanced the professionalism of the navy. While at the Academy, Porter worked to get the new naval monument built so that it could join the venerable Tripoli Monument at Annapolis. He collected contributions from Naval officers and seamen totaling $9,000 and sketched out the design of the monument himself. Sculptor Franklin Simmons (1839-1913), who also sculpted the equestrian figure of General John A. Logan at the center of Logan Circle, was hired to carve the figures for the monument in fine white Carrara marble in his studio in Rome. So far so good. A reading of the National Register listing for Civil War monuments in Washington suggests that the ensuing production of the memorial was accomplished with efficiency and purpose: “The sculpture was erected by the government with contributions from Navy personnel under a Congressional Act approved July 31, 1876 (19 Stat. 114). It was sculpted and carved in Rome in 1877 and dedicated in the same year.”

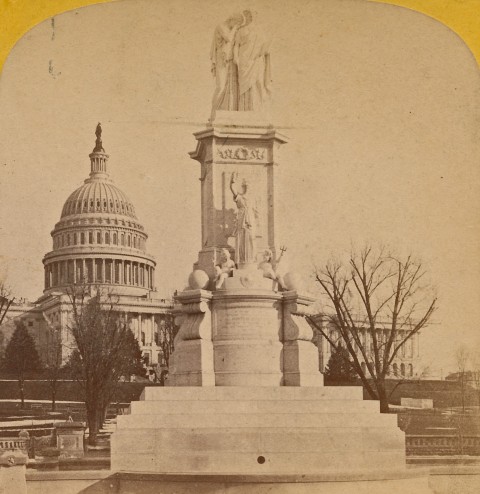

The Peace Monument c. 1880, from a stereoview in the author’s collection.

However, things didn’t really go quite that smoothly. For one thing, it seems that Admiral Porter and Secretary Welles may not have gotten along well together. According to retired Navy officer C.Q. Wright, who wrote about the Peace Monument in the Washington Post in 1923, “the few surviving letters which passed between [Porter and Welles] concerning the location of this monument seem to indicate indifference in the mind of Mr. Wells to the erection of the monument or a quiet disapproval of the affair in which he may have thought he saw sign of the high-handed self-assertion of Admiral Porter.” Wright suggests that friction between Porter and Welles may have led to changes both in where the memorial was to be placed and how it was to be designed.

Continues after the jump.

A contract with sculptor Simmons had been signed in 1871, and the Baltimore Sun reported in 1873 that Simmons was making good progress and was expected to finish the work in about two years. The monument at that time was a straightforward paean to the war’s lost naval heroes. It included two allegorical figures atop a grand 40-foot pedestal: America (or perhaps it is Grief) weeping for her lost sons on the shoulder of History, who records the names of the heroes for all time in a book. On the front of the pedestal a third figure, representing Victory, holds a laurel wreath over two smaller cherubic figures representing Neptune (the Navy) and Mars (the Marines). According to the Sun, once completed, the monument would “be conveyed to Annapolis in a man-of-war.”

The front (western) side of the memorial. Photo by the author.

Detail of the figures of America (Grief) and History.

But the monument never made it to Annapolis, and its warlike theme was modified. In 1876, an addendum to Simmons’ contract was signed adding a new figure on the back side of the pedestal representing Peace, holding an olive branch and overlooking symbols of agriculture and the arts and sciences. Once the sculptural work was finished in 1877, the pieces were shipped to the Washington Navy Yard aboard a freighter called the Supply. Annapolis was no longer the destination, and no man-of-war ever brought the sculptures over from Italy. Congress pitched in $20,000 to have a large pedestal built for the monument, including a surrounding basin built on a raised platform, and the monument was now destined to be constructed at the foot of the Capitol. Edward Clark, the architect of the Capitol, designed the base.

Victory, with Mars and Neptune at her feet.

Construction began in the spring of 1877, but the memorial was never really finished. According to Keim’s Illustrated Handbook of Washington and Its Environs (1883), it was supposed to include a decorative fountain around its base and four street lamps at the corners. “Cascades flow from the mouths of bronze dolphins in the sub-base, and four artistic lamp posts stand at the rim of the basin,” Keim writes. Keim seems to have based his description on the proposed design of the memorial rather than the completed structure, because these decorative elements were never built. Instead, the marble base of the pedestal includes four bare holes that dump water out into the surrounding basin, and the four granite piers that were meant to hold the “artistic” lampposts have naked screws sticking out of them, waiting patiently (for 135 years now) for the lampposts to be installed.

The pedestal, basin and granite piers for lampposts.

One of the unfinished granite lamppost piers.

Wright speculates that the project ran out of money before the bronze dolphins and lampposts could be fabricated, but it seems clear from the unfinished construction that they were expected to be added in short order. Keim’s Handbook notes that the 44-foot monument was “erected without ceremonies” in 1877. Presumably a formal dedication was put off until the memorial could be completed. Since that never happened, it appears that the monument was never formally dedicated.

Interpreting the thematically complex monument—the grieving pair at the top, Victory on one side, Peace on the other—was challenging even at the time it was built. As early as May 1877, while the monument was still under construction, the National Republican felt compelled to publish a clarification about its meaning:

The misnomer “Statue of Peace” is applied to the structure now under process of erection at the intersection of Pennsylvania avenue and First street, at the foot of the Capitol ground. It isn’t a “Statue of Peace.” It is a monument to commemoriate the deeds of our navy during the war of the rebellion…

An Evening Star reporter queried one of the German laborers working on the monument as to its meaning. “Vell, I don’t can tell you vot dem vimmens is already, but I tink dey be officers’ vives.” the laborer supposedly replied. “One of dem vimmens, de one what cry all de time, she just heard dot her husband got wounded, and she feel awful bad about dot, and she don’t can write, so she get de udder vimmen mit de fedder pen to write a letter for her.”

Though many people greatly admired the towering memorial, it had plenty of detractors as well. The sorrowful figure of America, hanging on the shoulder of History, seemed a bit maudlin even in Victorian times. The Star formally reviewed the monument in June 1877 and found much to be desired.

For a work of its importance, it is deficient in originality and power; but it is likely that the artist was in some degree hampered in his efforts, since it is given out that the design is in whole or in part that of a high naval officer—who probably knows a good deal more about the high seas than he does about high art.

The Star reviewer went on to liken it to cemetery memorials “which rich and disconsolate husbands who marry again in a year or two are in the habit of erecting over the graves of their recently deceased wives.” Last but not least, the siting was criticized, as the monument seemed to be overwhelmed by the Capitol building behind it. It would have fared better “against rich green foliage or the clear blue sky, like the splendid Scott statue in the 16th street circle.” The Post would comment some years later that “it is quite the most depressing and lugubrious bit of marble that we can remember having seen anywhere outside of a graveyard.”

The figure of Peace on the rear (eastern) side of the monument.

As it was being sized up in the press in 1877, the monument was far from complete. In January 1878, the Star reported that “The Naval Monument has just been completed by putting in place the figure of Peace.” Of course, the bronze fixtures at the base remained missing. The Star’s reporter had a very different view of the monument than his colleague who had offered the sarcastic comments the previous summer. This time the Star wrote:

The whole composition of the work is new, and quite unlike any other memorial erected to commemorate the Civil War. The composition and the general simplicity of the design and execution of the drapery shows that the artist made a careful study of the best models of antiquity, and endeavored to form a style after the best principles of classic art. This group, when it was completed by Mr. Simmons in his studio at Rome, excited great interest among the artists of all nations, and it was generally spoken of as one of the most original and satisfactory works of our time.

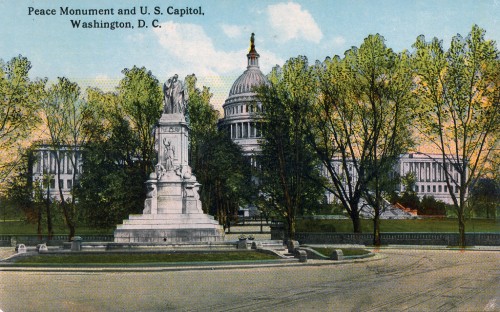

Postcard view of the monument in the 1910s (author’s collection).

Masterpiece or not, the monument has languished at the foot of Capital Hill ever since. In the late 19th century, before so much of the surrounding area was turned into empty green space, this was a rather desolate and unsafe neighborhood. In 1884, a certain John L. Ransom was attacked and robbed under the tranquil gaze of the Peace Monument’s figures after he had emerged from nearby Bryan’s Saloon. A letter to the editor of the Post in 1894 complained that the monument had become “rather a tramp headquarters than a monument to the beautiful angel of peace.” A trolley car employee, “under a greasy umbrella” stood watch over a “horrible pit,” with a stable just behind the monument filled with the “spavined skeletons” of the horses who dragged trolley cars, known as herdics, up Capitol Hill. What’s more, “the water basin surrounding the monument has long been dry, and is a convenient receptacle for the garbage collected by wind and weather instead of being the handsome fountain and pool which it was intended to be.” The following year a fight erupted at the base of the monument between Edward Lackey and Charles Ward, two men “well known to the police” over who should pay their trolley fare. Lackey’s hand was slashed, and both men were thrown in jail. Grief, History, Victory, and Peace all looked on, unmoved.

The Peace Monument c. 1910, still a trolley stop (Source: Library of Congress).

As early as 1892, there was talk of moving the monument, perhaps to the small park at Connecticut Avenue and Q Street, NW. Fortunately, that didn’t happen. Later suggestions were made to move it to Arlington National Cemetery or even the Naval Academy in Annapolis, where it was supposed to go in the first place. No action was taken.

In 1904, the Army was given the responsibility for maintaining the memorial as the surrounding areas were cleaned up, cleared of railroad tracks, saloons, stables, canal remnants, and other structures, and the modern pristine landscape was created.

Postcard view of the monument in the 1910s (author’s collection).

By 1903, the ravages of time and weather were already apparent, with several of the figures showing holes and chipped pieces. The Post even alleged that the statues had been made of Keene cement rather than Carrara marble, thus leading to rapid erosion, but there is no other evidence to support this claim. A 1931 Post article further sounded the alarm about extensive acid erosion to the Peace Monument and other DC landmarks.

Little, if anything has been done over the years to preserve the never-finished monument, and the marble figures are now badly eroded. It appears that a chunk of marble broke from the side of the head of History at one point, and a clumsy repair was made. The faces of all of the figures have worn down to the point that they seem to have a vague, ghostly presence. The left arm of Peace broke off at one point and has been repaired. The right arm of the cherubic Neptune also broke off but was never replaced.

The faces of America and History as they appear today (photo by the author).

The Post recently chose, fittingly, a beautiful photo of the Peace Monument to represent our collective desire to commemorate those who have been victims of senseless violence, as occurred in Newtown, Connecticut. If such memorials are indeed important to us, we may want to consider taking steps to preserve our grand Peace Monument—and perhaps even finish the parts of it that have been left undone for 135 years.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included: George Rothwell Brown, Washington: A Not Too Serious History (1930); Federal Writers’ Project, Washington City and Capital (1937); James M. Goode, Washington Sculpture (2008); B. Randolph Keim, Keim’s Illustrated Hand-Book: Washington and Its Environs (1883); the National Register listing for Civil War monuments in Washington; and newspaper articles.

Recent Stories

For many remote workers, a messy home is distracting.

You’re getting pulled into meetings, and your unread emails keep ticking up. But you can’t focus because pet hair tumbleweeds keep floating across the floor, your desk has a fine layer of dust and you keep your video off in meetings so no one sees the chaos behind you.

It’s no secret a dirty home is distracting and even adds stress to your life. And who has the energy to clean after work? That’s why it’s smart to enlist the help of professionals, like Well-Paid Maids.

Unlock Peace of Mind for Your Family! Join our FREE Estate Planning Webinar for Parents.

🗓️ Date: April 25, 2024

🕗 Time: 8:00 p.m.

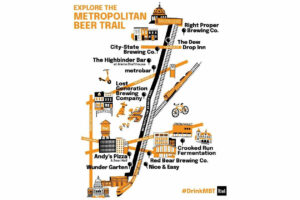

Metropolitan Beer Trail Passport

The Metropolitan Beer Trail free passport links 11 of Washington, DC’s most popular local craft breweries and bars. Starting on April 27 – December 31, 2024, Metropolitan Beer Trail passport holders will earn 100 points when checking in at the

DC Day of Archaeology Festival

The annual DC Day of Archaeology Festival gathers archaeologists from Washington, DC, Maryland, and Virginia together to talk about our local history and heritage. Talk to archaeologists in person and learn more about archaeological science and the past of our