Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Around the turn of the last century city planners and others worried that the nation’s capital did not have a suitably grand and dignified meeting hall where large assemblies and conventions could gather and celebrate the greatness of America. A spacious 6,000-seat convention hall had been built in Mount Vernon Square in 1875 (see our previous profile), but it was in the old red-brick Victorian style and too far removed from the Mall to satisfy the aspirations of the Beaux Arts generation. The new imperial, white-marble Washington, as envisioned by the McMillan Commission, needed a massive and powerful-looking auditorium with a forest of imposing classical columns lining its facade. At least Susan Whitney Dimock (1845-1939), a New York socialite, certainly thought so, and she made it her life’s work to have such a meeting hall built. But despite endorsements from several presidents and countless other powerful people, the hall was never meant to be.

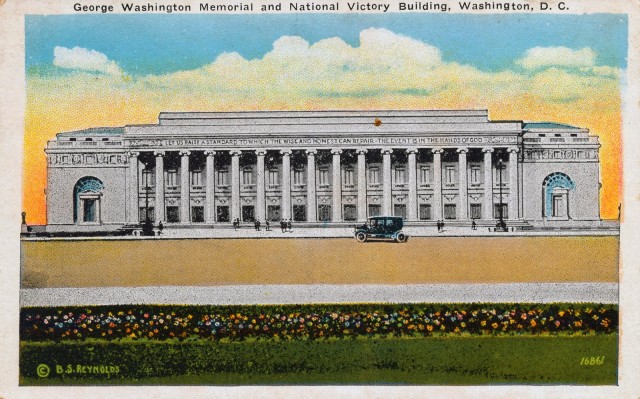

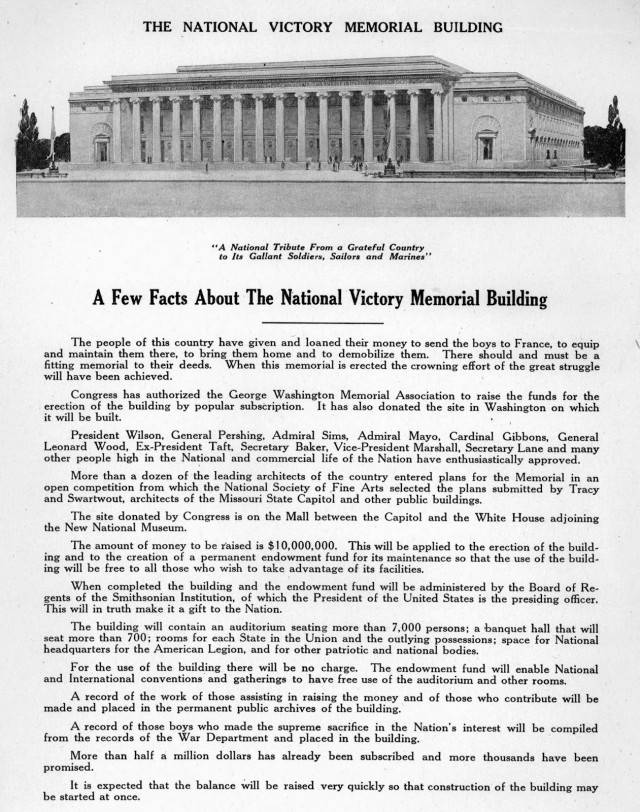

Postcard of the planned memorial from the 1920s (author’s collection).

Dimock was born to the wealthy Whitney family of New York, the daughter of James Scollay Whitney (1811-1878). Two of her brothers became successful and powerful industrialists in an age of industrialists. She married Henry F. Dimock (1842-1911), a New York attorney who also became a prominent businessman, working in large part with Whitney family interests. Susan clearly wished to leave her own mark for the betterment of the country, and she set her sights on a memorial to George Washington—never mind that one already had been completed in 1884.

Whitney was the president of the George Washington Memorial Association, founded in 1898 to promote the construction of an educational institution in Washington to commemorate the first president. The intention was to supply headquarters and meeting space for “every scientific, educational, patriotic, art and literary organization in the United States, thus making the capital city the nerve center of a monster force which shall aid in consummating [George] Washington’s earnest wish and injunction laid upon the nation for the ‘promotion of science and literature’ and the ‘general diffusion of knowledge,'” according to a notice printed in the Baltimore Sun in 1909.

The Association had signed an agreement with the Columbian College in 1904 to build a memorial to George Washington on land the College had acquired at Constitution Avenue and 17th Street NW, but the deal fell through. While the Columbian College went on to become the George Washington University, the association changed course and began working to get its memorial built on the Mall. The plan was that the Smithsonian would take over maintenance and operation of the building once it was constructed by the association.

Susan Whitney Dimock (Source: Library of Congress).

The association sought to raise funds through subscriptions of one dollar each. By 1909 it had $25,000 in its permanent fund—with a goal of $2 million. In arguing for the massive new building, an article in the New York Times noted the pressing need for convention space in the capital: “It is pointed out that when the famous International Tuberculosis Congress met last Fall in Washington there was no building suitable for such a gathering. When the International Congress of Waterway Engineers, which has been invited by Congress to hold its next convention in Washington, comes along there will be no hall with adequate meeting and office rooms.”

While fundraising continued at a modest pace, Dimock kept thinking of ways to honor George Washington. In 1912 she proposed that a memorial highway be constructed from D.C. to his home at Mount Vernon, a vision that would later be carried out with the George Washington Memorial Parkway. But her primary objective was always the building on the Mall. A breakthrough came in 1913 when Congress passed legislation setting aside the land on the Mall vacated by the removal of the old Baltimore & Potomac (Pennsylvania Railroad) station for construction of the memorial. By then the association had some $250,000 in donations and pledges, according to newspaper articles. That same year the recently-widowed Mrs. Dimock decided to move permanently to Washington, and she acquired property at New Hampshire Avenue and Swann Street NW to build her home.

In 1914 the venerable Beaux-Arts architectural firm of Evarts Tracy (1868-1929) and Egerton Swartwout (1870-1943) produced a stately, neoclassical design for the proposed memorial. The planned building featured a main auditorium seating 7,000, a banquet hall seating 600, and multiple smaller meeting rooms set aside for various organizations. The auditorium’s dome would be three time the diameter of the dome of St. Peter’s in Rome.

But there were many more hurdles to overcome before the hall could be built. The association’s congressional charter required it to raise $1 million and begin construction by March 15, 1915, a goal it could never hope to meet. Dimock blamed the onset of World War I for missing the deadline. “Under ordinary circumstances the site [on the Mall] would be forfeited if we did not have the $1,000,000, but war has prevented many subscribers from paying their subscriptions to the fund. Congress recognizes this fact. Originally it was planned that the building should be reared by small contributions from many persons, but in this crisis the process is too slow. The second million, to complete the estimated cost of the whole and decorate the seven auditoriums planned to diverge from the main auditorium, will come from the small subscribers. Already more than 45,000 school children have contributed to the cost of one wing reserved for child welfare work by purchasing ten-cent pins inscribed ‘A brick in the George Washington Memorial Building.”

The years kept rolling by, and Dimock kept working to raise money. She was more successful at garnering endorsements from political leaders, including president Woodrow Wilson and former president William Howard Taft in 1917. Everyone agreed that the proposed grand meeting hall was needed, and everyone was happy to pledge their moral support for the association’s efforts to raise the needed funds (which had grown to $3 million).

Dimock seems to have had boundless energy and devoted much of it to a variety of charity efforts connected with the war. An article in the New York Sun in 1918 called her “almost the last of a group of Washington grandes dames, women of tremendous social influence who ruled Washington for the salvation of its social soul…” By 1919, with the war over and the memorial still not even started, she reinvented it as the National Victory Memorial to commemorate the success of American doughboys in the Great War (it would still also honor George Washington). The immense dome of the auditorium now was to be inlaid with four million stars, one for each American to serve in the war. The project gained new momentum, but its financial goal had risen to $10 million, moving it farther away than ever.

An appeal to fund the memorial from 1919 (Source: Library of Congress).

Finally on November 14, 1921, a grand cornerstone-laying ceremony was held, with President Warren G. Harding (another staunch verbal supporter) doing the honors. After the ceremony construction work was begun, with a concrete foundation poured and stairs laid out. A fence was built around the site. Then work stopped for lack of funds.

More appeals went out throughout the 1920s. The goal was put out that the memorial be completed in time for the bicentennial of George Washington’s birth in 1932. But by that time the only new development was a lawsuit by architect Egerton Swartwout for $166,036. His firm had never been paid for the design of the memorial.

Finally in 1937 the project was abandoned for good. The concrete foundation work was removed and the site turned over to the newly-established National Gallery of Art, which had had $10 million in construction funds from Andrew Mellon (1855-1937). The Gallery’s majestic building, designed by John Russell Pope (1874-1937), was completed on the site in 1941.

Dimock had died in 1939, never having seen her dream project to fruition. Probably few people would argue that the art gallery was not the best use for its prime location on the Mall. Nevertheless, Washington would continue to lack large convention space for much of the 20th century. -And what became of the thousands of dimes contributed by America’s schoolchildren for bricks in the George Washington Memorial? An excellent question.

Recent Stories

For many remote workers, a messy home is distracting.

You’re getting pulled into meetings, and your unread emails keep ticking up. But you can’t focus because pet hair tumbleweeds keep floating across the floor, your desk has a fine layer of dust and you keep your video off in meetings so no one sees the chaos behind you.

It’s no secret a dirty home is distracting and even adds stress to your life. And who has the energy to clean after work? That’s why it’s smart to enlist the help of professionals, like Well-Paid Maids.

Unlock Peace of Mind for Your Family! Join our FREE Estate Planning Webinar for Parents.

🗓️ Date: April 25, 2024

🕗 Time: 8:00 p.m.

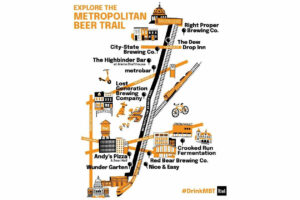

Metropolitan Beer Trail Passport

The Metropolitan Beer Trail free passport links 11 of Washington, DC’s most popular local craft breweries and bars. Starting on April 27 – December 31, 2024, Metropolitan Beer Trail passport holders will earn 100 points when checking in at the

DC Day of Archaeology Festival

The annual DC Day of Archaeology Festival gathers archaeologists from Washington, DC, Maryland, and Virginia together to talk about our local history and heritage. Talk to archaeologists in person and learn more about archaeological science and the past of our