Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

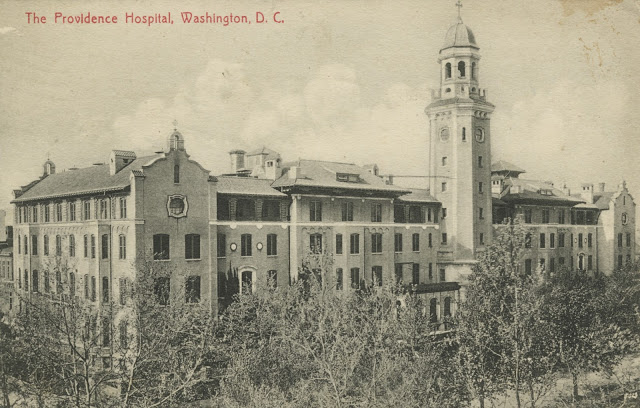

Providence Hospital on Capitol Hill, circa 1910 (author’s collection).

Just a few blocks south of the Library of Congress once stood the city’s largest and most prestigious hospital, founded in the urgent, needy days at the dawn of the Civil War. Because the modern Providence Hospital is now located in Brookland, it can be easy to forget how important this institution was for the rapidly growing central city in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Providence pioneered modern hospital practices at a time when Washington sorely needed them.

Before Providence, there was only one hospital in the city, and it was a rather sorry one–the Washington Infirmary on Judiciary Square, which had been converted from an old jail in the 1840s. In April 1861, after war was declared, this hospital was taken over by the military, and a new hospital for the general population was urgently needed. The Roman Catholic Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul had been busy opening hospitals throughout the U.S., and Sister Lucy Gwynn (1800-1865) spearheaded the effort to start a hospital in Washington. Gwynn persuaded the descendants of Daniel Carroll, one of the original major landowners of Washington, to donate the old Nicholson Mansion at 2nd and D Streets, SE, for the hospital’s use and convinced Dr. Joseph M. Toner (1825-1896), a leader among the city’s physicians and the future founder of the Columbia Historical Society, to serve as its first formal head.

The original hospital in the Nicholson mansion.

The sisters opened their hospital a month before the Battle of Bull Run, the first major engagement of the war, when no one was imagining yet what horrors would await medical facilities like Providence. A notice in The National Intelligencer about the opening of the hospital paints an idyllic picture:

The [Nicholson Mansion] is large and airy, the location high and healthy, and the grounds extensive and beautifully ornamented with shade and fruit trees, and gravelled walks. We can imagine what a relief it would be to the invalid to be transferred from the hot and dusty city to the grateful shade of this cool and quiet retreat.

It didn’t work out quite like that. After Bull Run and subsequent Civil War battles, the wounded began pouring into Washington. Numerous temporary hospitals were quickly established in converted churches and hotels, and government buildings were requisitioned as infirmaries throughout the city. The Washington Infirmary, the city’s only other permanent hospital, burned to the ground in November 1861 and was never reconstructed. At Providence, the beautifully ornamented grounds were soon full of tents groaning with the wounded, as the hospital building itself could accommodate very few patients. The “high and healthy” perch on Capitol Hill became known as Bloody Hill as Providence cared for countless soldiers from both the North and the South throughout the conflict.

After its wartime baptism by fire, Providence continued as the city’s preeminent hospital under the leadership of Sister Beatrice Duffy (circa 1827-1899), as well as Dr. Toner, who served as the house physician. A Congressional charter in 1864 was followed by several appropriations that allowed the hospital to begin constructing a large new building in 1866.

The 1872 Providence Hospital building

Completed in 1872, the Second Empire-style main hospital building had a rather stiff, institutional look. Architectural historian James Goode has described it as combining a “bracketed” Italianate vocabulary–wide-bracketed eaves, a flat façade and heavy lintels–with Second Empire motifs, such as a mansard roof and delicate ornamental ironwork cresting.

With 250 beds, the hospital remained the largest in Washington through the turn of the century, despite the arrival of a number of competing institutions. Providence offered a range of accommodations, from indigent wards (simple beds lined up in large halls) to private suites, complete with bedroom, bath and large parlor with fireplace, at a cost of fifty to seventy-five dollars weekly. The use of varying types of accommodations based on ability to pay was typical of the time.

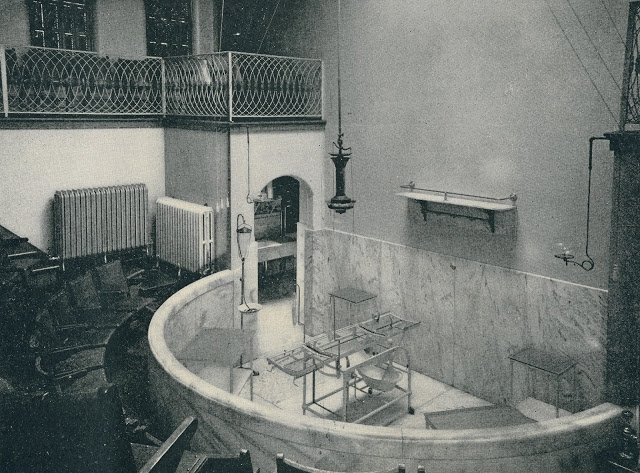

Providence made many innovations in those days. Whereas other hospitals had “closed staff,” restricting patient care to their own physicians, Providence had an “open staff” policy, allowing patients’ own doctors to come in and care for them while they were admitted to the institution. It became a teaching hospital, opening the first surgical amphitheater in 1882, where Georgetown University medical students first studied before their own hospital was built. The city’s first contagious disease ward was opened at Providence in 1895, the first outpatient clinic in 1907, and first cardiac unit in 1908.

The remodeled and enlarged 1904 hospital building (author’s collection).

By the 1880s, the once capacious hospital was becoming crowded. In 1886, The Washington Post noted, apparently with alarm, that “[s]o urgent are the demands upon the hospital that the wards originally set apart for colored patients exclusively are used by both white and colored, the same being the case in the female ward.” New buildings were added, including a separate building for the contagious ward in 1899 and a nurses’ home in 1901. With federal funds, the hospital was finally able in that same year to embark on a substantial expansion program, completely remodeling and enlarging the existing building and extending it eastward, filling up the entire city square.

The makeover, completed in 1904, was thorough both outside and in, with the former Second Empire building being transformed into a much larger Mission-style structure, a type of design being adopted for hospitals across the country, including the previously profiled Columbia Hospital for Women. Prominent Washington architect Waddy B. Wood (1869-1944) was responsible for this transformation, which gave the building tiled roofs, stuccoed walls and a soaring 175-foot central bell tower. Inside it was finished in a dignified–and clean-looking–white marble. The cost was a staggering $530,000.

A corridor of the new hospital (Source: The New Providence Hospital March 15, 1904).

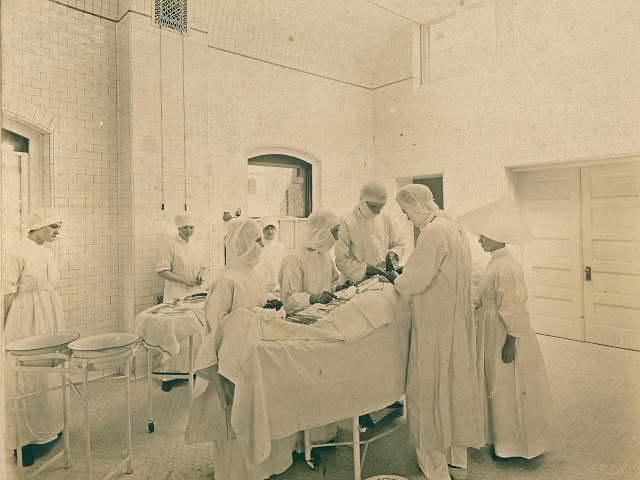

A dazzlingly white operating room in the new hospital, circa 1904 (Author’s collection).

An amphitheater-style operating room, used for teaching (Source: The New Providence Hospital March 15, 1904).

Bedroom of a private suite (Source: The New Providence Hospital March 15, 1904).

Patients and nurses in the free ward (Source: Library of Congress).

An ambulance, from the 1910s (author’s collection).

The Daughters of Charity used Providence as a training ground for nurses, and these sisters ventured to the battlegrounds of the Spanish-American War and World War I to treat wounded soldiers, some of whom were then brought back to the hospital for convalescence. After the armistice ended World War I, large numbers of convalescing soldiers stopped at Providence before returning home.

Hospital staff (author’s collection).

A group of interns pose outside the hospital in 1916 (author’s collection).

After the U.S. entry into World War II, the population of the District mushroomed, and the infrastructure of the aging hospital was soon taxed to its limits. In February 1942, The Washington Daily News reported that the obstetrics ward was lined with gurneys holding women who had just delivered babies or, in one case, were in the process of delivering, no hospital beds being available. Two more new mothers had to make do sitting in chairs. Six years later, after the war had ended, another Daily News reporter found much the same situation: overcrowding throughout (including a former sun porch packed with beds) and outrageous inefficiencies. For example, at meal times, the elevator bank in one part of the hospital had to be closed off for passengers so that staff could use it to transport meals from the basement kitchen to rooms throughout the building. “We have great trouble keeping the food warm,” one of the sisters observed, in what must have been an understatement.

Plans were already being made by that time to build a new hospital at a new location to replace the outmoded facility. In 1949, a fifteen-acre site at 12th and Varnum Streets, NE, was acquired from the Catholic University of America, and in 1952 the proposed eight-story, 350-bed replacement hospital was announced. A federal appropriation for District hospitals had been passed by Congress in late 1951, jump-starting the project with more than half of the $8 million that would be needed. The firm of Faulkner, Kingsbury and Stenhouse designed the new facility in a restrained, Mid-Century Modern style. It opened in 1956 and continues in operation to this day.

Postcard view of the new hospital on Varnum Street NE (author’s collection).

Meanwhile, the site of the old hospital on Capitol Hill was destined for years of uncertainty as powerful competitors squabbled over its future. In the first years after moving, the Daughters of Charity kept ownership of the old building and leased it to the government. Then, in 1962, the organization sold the site for $670,000 to a partnership of four investors that included Max Bassin, founder of Bassin’s Restaurant. The new owners wanted to build a high-rise apartment complex on the site, but their request for a zoning variance to do so was denied. Several organizations, including the National Capital Planning Commission, went on record urging that the historic hospital building be preserved, but no one came forward with a practical proposal or the funding to turn that dream into a reality.

The old building grew derelict as time went by, and after the last Commerce Department tenants left in 1964, it was heavily vandalized. Parts of it reportedly made their way on to other properties across Capitol Hill. The District condemned the tattered building in 1965, and it was soon torn down. Next, the owners proposed a parking lot for the vast newly cleared square, but that request was quickly rejected. The government finally bought the property from the four owners in 1972 for $1.4 million, giving them a tidy profit. More years then went by as new proposals–a school for Congressional pages or a parking lot for Hill staff–were proposed and rejected. Finally, in late 1978, funds were committed to landscape the empty lot and convert it into the restful park that remains there today.

* * * * *

A version of this article previously appeared in Lost Washington D.C. (2011). Other sources included Mary Clemmer Ames, Ten Years in Washington (1882); District of Columbia Hospital Association, Heritage: Honoring Our Hospitals’ Early Years in the Nation’s Capital (2015); Constance McLaughlin Green, Washington, A History of the Capital, 1800-1950 (1962); Junior League of Washington, The City of Washington: An Illustrated History (1977); Providence Hospital, The New Providence Hospital March 15, 1904 (1904); Providence Centennial Book 1861-1961 (1961); and numerous newspaper articles.

Recent Stories

For many remote workers, a messy home is distracting.

You’re getting pulled into meetings, and your unread emails keep ticking up. But you can’t focus because pet hair tumbleweeds keep floating across the floor, your desk has a fine layer of dust and you keep your video off in meetings so no one sees the chaos behind you.

It’s no secret a dirty home is distracting and even adds stress to your life. And who has the energy to clean after work? That’s why it’s smart to enlist the help of professionals, like Well-Paid Maids.

Unlock Peace of Mind for Your Family! Join our FREE Estate Planning Webinar for Parents.

🗓️ Date: April 25, 2024

🕗 Time: 8:00 p.m.

Metropolitan Beer Trail Passport

The Metropolitan Beer Trail free passport links 11 of Washington, DC’s most popular local craft breweries and bars. Starting on April 27 – December 31, 2024, Metropolitan Beer Trail passport holders will earn 100 points when checking in at the

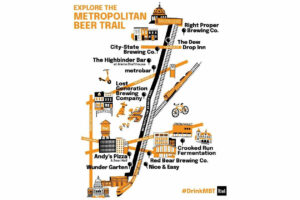

DC Day of Archaeology Festival

The annual DC Day of Archaeology Festival gathers archaeologists from Washington, DC, Maryland, and Virginia together to talk about our local history and heritage. Talk to archaeologists in person and learn more about archaeological science and the past of our