Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is also the author of Lost Washington DC.

Of Washington’s great hotels, the Willard is one of the most celebrated and easily recognized. Many people know that President Lincoln stayed at Willard’s before he was inaugurated in 1861. Others believe (incorrectly) that the word “lobbyist” was coined to refer to promoters of various causes who hung around the Willard’s lobby, hoping to buttonhole President Ulysses S. Grant for favors. But fewer realize how many incarnations the old hotel has had, that it began life as a rather mediocre hostelry, or that many of the famous events in its history occurred in a very different, earlier building.

Early view of Pennsylvania Avenue with the City Hotel on the right (Source: Library of Congress).

There has been a hotel on the northwest corner of 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, since 1818, almost three decades before the Willard brothers showed up to take over its operations. The prominent early Washington landowner, John Tayloe (1770-1828), whose elegant Octagon House is one of Washington’s great mansions, acquired this property and built a row of six townhouses here as an investment in 1816, renting out the corner building to be used as a hotel two years later.

Continues after the jump.

After a succession of early hoteliers, Azariah Fuller (1789-1848) took over in 1833, eventually calling his establishment the City Hotel, although most everybody knew it as Fuller’s. In those days it was not particularly distinguished, although it had grown in size by taking over adjoining townhouses, just as the nearby National and Brown’s Indian Queen had done. One of the earliest celebrities to stay at the hotel was Charles Dickens, who visited Washington during his American tour in 1842. Dickens was singularly unimpressed with Fuller’s (and pretty much everything else about Washington) and penned these memorable words about his stay:

The hotel in which we live is a long row of small houses fronting on the street and opening at the back upon a common yard, in which hangs a great triangle. Whenever a servant is wanted, somebody beats on this triangle from one stroke up to seven, according to the number of the house in which his presence is required: and as all the servants are always being wanted, and none of them ever come, this enlivening engine is in full performance the whole day through. Clothes are drying in this same yard; female slaves, with cotton handkerchiefs twisted round their heads, are running to and fro on the hotel business; black waiters cross and recross with dishes in their hands; two great dogs are playing upon a mound of loose bricks in the center of the square; a pig is turning up his stomach in the sun, and grunting ‘that’s comfortable’; and neither the men, nor the women, nor the dogs, nor the pigs, nor any exalted creature takes the smallest notice of the triangle, which is tingling madly all the time.

By 1847, Benjamin Ogle Tayloe (1796-1868), John Tayloe’s son and heir, had apparently grown dissatisfied with the condition of the hotel and was looking for a new manager. Hence Fuller was soon gone (he opened up the Irving Hotel down the avenue at 12th Street), and in his place Tayloe installed Henry A. Willard (1822-1909), a shrewd and energetic young entrepreneur whom Tayloe’s fiancée, Phoebe Warren, had recommended. A native of Vermont, Willard had learned the hospitality trade as a steward on a Hudson River steamboat, where he had impressed Miss Warren. He was eager for a new and challenging venture.

As part of the arrangement to bring Willard on, extensive improvements were made to the hotel, the first of its many rebirths. It was expanded to 150 rooms from 40 and had elegant gentlemen’s and ladies’ dining rooms, parlors, and three large halls in front, connected to the rooms above by two broad oak staircases. The building was thoroughly renovated again three years later with a new, continuous brick facade curving smoothly around the corner and up 14th Street. By this time Henry had turned to his brothers for help in running the burgeoning business. First to join him was older brother Edwin (1818-1863), who soon left to manage the National Hotel for several years before joining the army as a paymaster during the Civil War. After Edwin moved on, Henry brought in Joseph (1820-1897), who thrived as the hotel’s business manager and would eventually take complete control of the enterprise.

President-Elect Pierce, in carriage, leaving the Willard, 1853 (Source: Library of Congress).

In those days Henry was gunning for as much publicity and prestige as possible, and one thing he needed was a presidential stay. With the election of Franklin Pierce in 1852 he saw his chance. “I think I shall get General Pierce all right,” Willard wrote that October. “He has stopped with me before, and I am a Democrat and the National Hotel fellows are Whigs. I stand the best chance.” Pierce did indeed stay at Willard’s on the eve of his inauguration, fueling the hotel’s growing pre-eminence.

As the 1850s wore on, the brothers looked to gain ownership of their building and expand their operations. Apparently the hotel’s early success was more than Benjamin Ogle Tayloe had imagined, and he balked when the Willards wanted to make good on the purchase option of their lease. The brothers filed suit and finally succeeded in acquiring the valuable property when the Supreme Court ruled in their favor. They also acquired the large adjoining tract along 14th Street that extended north to F Street. With additions to the original buildings that filled the length of the block, Willard’s was soon the most important hotel in the city.

Of course, being in the spotlight can bring notoriety as well as prestige. Such was the case in May 1856 when Philemon T. Herbert (1825-1864), a member of the House of Representatives from California, was staying at Willard’s. Herbert, a native of Alabama, apparently had a very combative personality. It seems he wanted breakfast served to him at 11:30 one morning and was told by a young servant that a special order would be needed because it was so late. According to the Evening Star, Herbert told the boy to “Clear out, you Irish son of a bitch,” and then “turned to another waiter, Thomas Keating, who was standing near by, and exclaimed ‘And you, you damned Irish son of a bitch, clear out, too.'” Soon Herbert and Keating were in an all-out fight, Herbert striking Keating on the neck, Keating throwing a plate at him, and Herbert retaliating with a thrown chair. Other waiters quickly joined the fray. “The struggle now became intensely exciting,” the National Intelligencer reported, “and as it proceeded crockery and chairs were broken profusely by the parties to the contest.” It was only when the combatants were finally pulled apart that Herbert suddenly drew his pistol and shot Keating in the chest, killing him instantly.

The subsequent trials (there were two) of Rep. Herbert for the murder of Keating were closely watched by the local Irish community, which feared that justice would not be served. The victim was an Irish immigrant, the accused a powerful California politician. Their concern was justified; Herbert was indeed acquitted, despite conceding that he had killed Keating. District Attorney Philip Barton Key (1818-1859), son of Francis Scott Key, was no match for Herbert’s powerful and well-paid attorneys. Nevertheless, Herbert gave up his political career after the publicity died down and moved to Texas. During the Civil War he would join the Confederate army and die of wounds sustained in battle in 1864.

Lord Napier, photographed by Matthew Brady (Source: Library of Congress).

Three years after the Keating affair, the Willard hosted one of the most elegant and celebrated social events in the city’s history, the farewell ball for Lord Francis Napier (1819-1898) of Great Britain, and his wife, Lady Anne Napier. Lord Napier, a well-liked minister, had reportedly been called home at President Buchanan’s request. Senator William Seward (1801-1872), who would later serve as Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of state, was miffed at the rebuke to the Napiers by his political rival Buchanan and was said to have organized the ball in retaliation. Whatever its impetus, the ball was a sensational event, one of the largest ever given in Washington City, with some 1,800 guests paying a steep ten dollars each to get in. The Intelligencer was pleased to note (a bit naively) that the ball was “perfectly free from all sectional, political, or local bias. There was no North, no South, no Republicanism, no Democracy in it.”

The Napier Ball, as depicted by Harper’s Magazine (Source: Library of Congress).

The 150-foot ballroom, draped in British and American flags and adorned with portraits of George Washington and Queen Victoria, was barely big enough to contain all the revelers. In fact, it was “so densely crowded that it required great exertions on the part of the floor committee to arrange for the dancing to commence,” however, commence it did around 11 pm. “The array of female youth and beauty combined was perfectly bewildering to hundreds of the opposite sex,” the Star observed, with obvious relish. At midnight a curtain was raised on the adjoining dining room, which seated three to four hundred. “The supper and wines were upon a scale of magnificence such as is rarely seen at such an entertainment on this side of the Atlantic,” marveled the Star. “Immediately in front of Lady Napier stood a pyramid of confectionary six feet high…and ornamented at the top with the figure of Brittania; and another similar ornament, at a different part of the table, emblematical of the United States.” Dining went on for three full hours, until 3 am, and dancing continued virtually unabated until 4. President Buchanan (privately fuming, no doubt) stayed away. For weeks afterward, the magnificent ball was the talk of the town, at least outside of the White House.

The Napier Ball was one of the last big events to take place in the hotel itself, and the crowded conditions made it imperative for the Willards find additional meeting space. That same year (1859), the Willards bought the former 2nd Presbyterian Church that adjoined the northern end of their property on F Street and converted it to a conference center, known as Willard Hall. Most public events after 1859 were held in Willard Hall, including the last-ditch peace conference convened there in February 1861, on the eve of the Civil War. As Adam Goodheart has eloquently described, the peace conference was doomed from the start. It was led by elder statesman John Tyler, a slaveholding southerner whose only claim to impartiality was that he was from a border state (Virginia) and was a former president. Many northern states refused to send delegates to the conference, which droned on for days with endless, inconsequential speeches. Perhaps the most dramatic event to occur at the Willard during the conference was not at Willard Hall at all. It was the furtive, unannounced arrival of president-elect Abraham Lincoln late in the night of February 22, 1861. Lincoln would later regret slinking into town (his advisers were convinced a plot was brewing against him), but he never regretted staying at Willard’s. In his haste he had forgotten to bring slippers, and Henry Willard went out of his way to borrow a pair for him from his wife’s grandfather. Lincoln returned the borrowed pair with his thanks, and the slippers became a prized Willard family memento. They are now in the Library of Congress.

The Willard in 1860 (Source: Library of Congress).

Lincoln soon moved into the White House, and Washington City was overrun with enthusiastic young military recruits, all eagerly awaiting a quick and glorious victory over the Southern rebels. Fortunately for the Willards, among the many regiments of volunteers that swarmed into the city early in 1861 were Col. Elmer Ellsworth’s “Fire Zouaves,” a troop of experienced New York City firemen. On May 9, 1861, a fire broke out in Samuel Owen’s tailor shop adjoining Willard’s, and it soon engulfed that building, threatening the hotel. Washington City firemen were nowhere to be found, but the Fire Zouaves appeared “in a twinkling,” according to the Star, and clearly enjoyed the opportunity to show off their skills in the heart of the Nation’s Capital. Borrowing equipment from nearby (and profoundly unresponsive) firehouses, they quickly gained control of the fire, impressing observers with their strength and dexterity. The Star noted one especially dramatic moment:

When the fire was at its height a small national flag fell from the rear of the building, attracting the attention of a squad of secessionists in the vicinity, who nudged each other, remarking, “There, there, that’s the way they’ll all go before long.” The Zouaves immediately caught up the flag and waved it, amid considerable cheering, while Mr. Willard ran up from his hotel two large flags, which the immense crowd greeted with a perfect roar of cheers, the Zouaves shouting, “They shall never be burnt; they shan’t come down.”

A grateful Henry Willard, whose hotel was saved from all but some water damage, gave Col. Ellsworth a handsome reward of $500 for the services of the Zouaves. Sadly, that money was soon spent to pay the expenses of the young officer’s funeral. He became the first official casualty of the war later in May when he was shot in Alexandria by an innkeeper after he took down a Confederate flag from the innkeeper’s house. It was one of the first indications that the war was real.

Hailing from Vermont, the Willard brothers were both staunchly Unionist. Joseph Willard decided to take a break from the hotel business to join the Union Army. Commissioned a captain, Joe Willard served on the staff of General Irvin McDowell. In April 1862 McDowell decided to set up temporary headquarters in Fairfax City, a staunchly Confederate town, and he sent young Captain Willard to the house of prosperous Edward R. Ford to inform the occupants they would be having unexpected company for several weeks. Willard soon met Ford’s flirtatious 23-year-old daughter, Antonia, an arresting beauty who was sophisticated beyond her years. The affable Vermonter proved no match for the wiles of this classic Southern belle. At 41 years old, he was soon madly in love with young Antonia and spent whatever time he could with her.

Joseph Willard, photographed by Matthew Brady (Source: Library of Congress).

Trouble is, Antonia was a spy, and a good one at that. She had been instrumental in alerting the Confederates to Union movements before the first Battle of Manassas. She was adept at getting Union soldiers to tell her details of their activities, which she dutifully relayed to rebel authorities. Dashing Confederate General J.E.B. Stuart had even named her his “honorary aide-de-camp.”

Antonia’s spying was uncovered in 1863, and she was arrested and thrown in the old Capitol Prison, where “Wild Rose” Greenhow was also held. Joe Willard pulled every string he could to get Antonia released, and he finally succeeded after seven months. Antonia agreed to renounce her spying and pledge an oath of allegiance to the United States, although Willard was the only person to witness it. Willard, in turn, under intense pressure from Antonia, resigned from the Army. They were married in 1864. However, the once-sprightly Antonia was frail and in poor health after her prison stay, and she died in 1871.

Union Army parade in May 1865. Willard’s is at left center (Source: Library of Congress).

The prosperity of the sprawling Willard complex continued well into the post Civil War years. These were the days when Mark Twain stayed at the Willard, writing satirically about the excesses of the Gilded Age. Ulysses S. Grant was president and a new optimism was in the air, despite the rife corruption. Grant liked to slip out of the White House in the evening and drop in on Willard’s for a drink or a smoke. He apparently liked being alone and supposedly complained about being hassled by “those damned lobbyists.” He didn’t make up the term “lobbyist,” however. It had been around for decades and was first used in London to refer to petitioners of members of Parliament.

The Willard brothers by this time were very wealthy and began to remove themselves from the everyday operations of the hotel, contracting out its management while still trying to ensure that their standards of quality didn’t deteriorate. There were actually four Willard brothers in the hotel business at one time or another in Washington. In addition to older brother Edwin, younger brother Caleb (1834-1905) was briefly involved in running the Willard Hotel in the 1850s. He also fought in the Civil War before acquiring the Ebbitt House hotel a block east of the Willard in 1864. All three surviving brothers built impressive homes on 14th Street in the blocks north of these two hotels after the Civil War.

Prosperous as they were, the brothers famously fell to disputing who owned exactly what. A complex network of real estate transactions involved each to varying degrees resulting in protracted quarrels and lawsuits. At one point the Willard Hotel itself was officially put up for auction so that Joseph could purchase it and claim full title to it. Henry Willard, still an entrepreneur at heart, then built the Occidental Hotel next door to the Willard on land that he owned. The Occidental became well known, especially for its elegant restaurant. Meanwhile, younger brother Caleb tried to expand his holdings on 14th Street next to his Ebbitt House hotel. Joseph owned a small lot just to the east of the Ebbitt. The story goes that Caleb offered to cover the lot with silver dollars as payment. Joe agreed, as long as the silver dollars were standing on edge. The deal never went through.

Joe, in fact, had for a long time been turning into a classic wealthy, reclusive eccentric. Ever since the death of Antonia in 1871, he was inconsolable, and he removed himself from everyday business affairs even as he grew fabulously wealthy. The rambling labyrinth of his hotel, once the height of fashion and prestige, grew outdated by the 1880s. Newer hotels, such as the posh Arlington and the magnificent Raleigh, began to easily outclass the old Willard. Nevertheless Joe was unwilling to make any changes. It was only with his death in 1897 that his heirs were finally free to undertake the radical move of tearing down the ramshackle old hotel and replacing it with a modern skyscraper.

The Willard today. This building didn’t exist until the 20th century (photo by the author).

The huge Beaux-Arts building we know as the Willard Hotel was the result. We’ll look next time at the prosperous life, near-death, and rebirth of that famous building.

* * * * *

Sources for this article included: Richard Wallace Carr and Marie Pinak Carr, The Willard Hotel: An Illustrated History (2005); Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, Willard’s of Washington (1954); Ernest B. Furgurson, Freedom Rising (2004); Dean R. Montgomery, “The Willard Hotels of Washington, D. C., 1847-1968” in Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Vol. 66/68 (1968); National Capital Planning Commission, Downtown Urban Renewal Area Landmarks (1970); John Clagett Proctor, Proctor’s Washington and Environs (1949); Henry Kellogg Willard, “Henry Augustus Willard: His Life and Times” in Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Vol. 20 (1917); and numerous newspaper and magazine articles.

Recent Stories

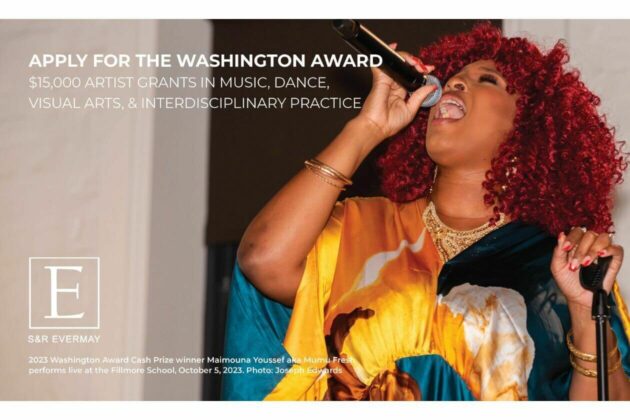

We are excited to announce that the 2024 Washington Award application opened today!

The 2024 Washington Award offers four cash prize awards of $15,000 for individual artists working in the field of music, dance, visual arts, and interdisciplinary practice (one award per category). This award, one of the largest grants in D.C. available to individual artists, provides unrestricted cash support to artists at critical moments in their careers to freely develop and pursue their creative ideas.

Since its inception in 2001, the Washington Award has recognized artists in music, dance, interdisciplinary practice, and visual arts. In a renewed commitment to supporting the artistic community of Washington DC, the Washington Award is eligible to DC artists who prioritize social impact in their practice.

Unlike our competitors, Well-Paid Maids doesn’t clean your home with harsh chemicals. Instead, we handpick cleaning products rated “safest” by the Environmental Working Group, the leading rating organization regarding product safety.

The reason is threefold.

First, using safe cleaning products ensures toxic chemicals won’t leak into waterways or harm wildlife if disposed of improperly.

DC Labor History Walking Tour

Come explore DC’s rich labor history with the Metro DC Democratic Socialists of America and the Labor Heritage Foundation. The free DC Labor History Walking Tour tour will visit several landmarks and pay tribute to the past and ongoing struggle

Frank’s Favorites

Come celebrate and bid farewell to Frank Albinder in his final concert as Music Director of the Washington Men’s Camerata featuring a special program of his most cherished pieces for men’s chorus with works by Ron Jeffers, Peter Schickele, Amy