Streets of Washington, written by John DeFerrari, covers some of DC’s most interesting buildings and history. John is the author of Historic Restaurants of Washington, D.C.: Capital Eats, published by the History Press, Inc. and also the author of Lost Washington DC.

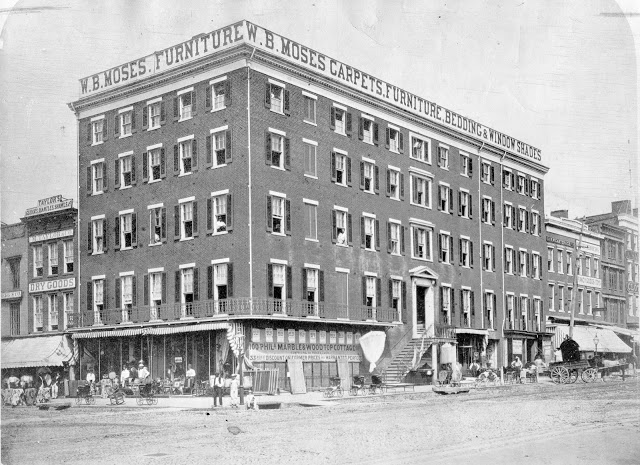

W.B. Moses and Sons store at 11th and F Streets NW, circa 1915 (source: Library of Congress).

“Sell Furniture Earth Over” was the headline in The Sunday Star in November 1908 profiling the W.B. Moses and Sons firm headquartered at 11th and F Streets downtown. By that time the company was well established as “the largest exclusively retail furniture carpet, upholstery, drapery, bedding and wall-paper house in America,” as one promotional book put it. Elegant W.B. Moses furnishings, many of them manufactured right here in the District, graced hundreds of homes throughout the Washington area and as far away as Panama City, Panama. Though the firm disbanded in 1937, antiques collectors still find mahogany chairs, dressers, and tables sporting the W.B. Moses label. Even the Senate Reception Room, one of the most richly decorated spaces in the U.S. Capitol, is fitted out with elegant Flemish oak benches custom made by W.B. Moses in 1899.

Descended from 18th century English immigrants, William Barnard Moses was born in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1834. At just four years old, he began living with his grandfather, a rope and fishing line manufacturer, from whom he learned basic business skills. At age 14 he had his first taste of the furniture business when he began working for his uncle in the finishing department of the Heywood Brothers firm in Gardner, Massachusetts. At age 21, he was ready to strike out on his own, accepting a position at the Ohio Chair Company in Cleveland, Ohio, where he headed up the finishing department. He married Rebecca McKnight there in 1858, and their first son, William “Willie” Henderson Moses, was born the following year.

Sketch of W.B. Moses from the April 27, 1889 edition of The Evening Star.

That same year Moses moved his young family to Philadelphia, where he collaborated with his brother, John Gardner Moses, and Philadelphia businessman, George L. Peckham, in a furniture wholesale business called Moses and Peckham. But the Philadelphia interlude didn’t last long. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Moses saw opportunity in Washington, D.C. He had heard about all the newcomers from the North swarming into the capital to replace the fleeing Southern-sympathizers. In December 1861 he moved to D.C. and found temporary space to open a new store in the Odd Fellows Hall on Seventh Street. Bringing three carloads of furniture from his old Philadelphia firm, Moses sold every piece before he could even put them all on display. He soon found larger quarters in the three upper floors of the Thorn Building at 508 Seventh Street NW, above Kenny’s grocery store. Then in 1865 he expanded into the adjoining building on the corner of 7th and D, where the National Intelligencer newspaper had formerly been headquartered.

Advertisement from the February 22, 1862 edition of The Evening Star.

In 1869 Moses moved to his first large building, the former Avenue House Hotel prominently located on Seventh Street across Market Space from the Center Market. The former hotel had seen a variety of commercial uses, and its layout proved perfect for Moses. Rather than lining up furniture in rows as other retailers had been doing, he fitted out complete display rooms—parlors, bedrooms, dining rooms, and kitchens—offering all items on display for sale, including wallpaper, carpeting, and even custom decorative finishes. Fronting directly on Market Space—the open plaza in front of Center Market that formed the epicenter of retail merchandising in 19th century Washington—Moses’ store was poised to do a booming business. His company quickly grew to become the largest exclusive furniture, carpeting, and upholstery store south of New York. Moses didn’t worry that his merchandise had the reputation of being the priciest in the city; he insisted the quality was worth it, and his customers agreed.

View of the Avenue House at 7th Street and Market Space NW, circa 1870 (photo courtesy of The Historical Society of Washington, D.C.).

While not the only furniture store in the city, W.B. Moses was the most prominent and gained an exclusive following. Presidents who bought furniture for the White House from W.B. Moses included Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, Chester A. Arthur, Warren G. Harding, and Woodrow Wilson. Julia Grant was a frequent patron, and it was said that all of the salesmen liked to wait on her because of her gracious manner.

Eldest son Willie had been sent to Europe for a classical education, and after returning he joined his father’s firm on his 21st birthday as head of the upholstering department. The company’s name was changed to W.B. Moses and Son; young Willie would go on to lead the company through its most prosperous years.

Perhaps the most dramatic advance was in the spring of 1884, when father and son began construction on a new, seven-story building on the southwest corner of 11th and F Streets NW. It was a bold move at the time. All of the city’s largest commercial businesses were still firmly entrenched on Pennsylvania Avenue. F Street was still an outpost lined primarily with private residences and small specialty shops. But the big store thrived in its new location. Three years after it opened in October 1884, the Woodward and Lothrop department store followed suit, moving to a new building on the opposite corner of 11th and F. In the coming decades F Street would replace Pennsylvania Avenue as the city’s major retail corridor.

Upholsterers at work at W.B. Moses and Sons, circa 1915 (source: Library of Congress).

The new building was designed by famed architect Alfred B. Mullet (1834-1890), the former Supervising Architect of the Treasury who had designed the extraordinary State, War, and Navy Building, which was still under construction when the Moses building went up. Elegant and imposing, the Moses building was finished in Philadelphia pressed brick and equipped with the latest technological advances, including electric lighting and two “quick-moving” elevators. Wrought iron frontage along F Street enclosed a 28-foot stretch of huge plate glass windows—a novelty at the time—that showed off elegantly decorated model rooms complete with every Victorian accessory. “You will look at them for the same reason you look at the pictures in an art gallery,” a boosterish 1908 Star article insisted. “They do not look ‘commercial’ at all, but remind every one of all that is beautiful and comfortable and fresh and clean in a home.” A heavy wrought-iron cornice topped the structure, surmounting an attic story fitted with large ocular windows.

Delivery vans parked on 11th Street outside of W.B. Moses and Sons, circa 1915 (source: Library of Congress).

It’s difficult to imagine how striking this building was at the time for its sheer height. At an open house on October 6, 1884, more than 500 people ascended to the roof to take in the view. A reporter for The Daily Critic described his impressions:

Since April 1 the old buildings at the southwest corner of Eleventh and F streets have disappeared and in their place the immense Moses building has risen with its seven lofty stories, towering up above all the private buildings in the city, leaving even the roof of the Franklin School building, on its hilltop, on a lower level, climbing higher than the State Department roof and looking down upon the little buildings clustering on every side.

The elevator trip to the top of the building seems like ascending the monument, but when the roof is reached and the grand panorama is spread below one’s feet the scene is inspiring and impressive. More than one hundred feet below the tide of humanity ebbs and flows on F street, while all around the city spreads out to the surrounding hills, and looking down upon the house tops a bird’s eye view is obtained unequaled from any other point of observation in the city.

The store featured high-quality reproductions of many classic furniture styles, from the “stolid style of Flanders” to the gilded excesses of Louis XVI. The Star claimed that Moses’ Elizabethan chairs were “so much of her blustering time that Sir Walter Raleigh could sit in one and smoke his famous pipe and never suspect that he was at 12th and F streets in Washington.” For those not taken with reproduction furnishings, there were contemporary styles as well, including many Craftsman pieces.

Carpets included “the richest Scotch and American Axminsters, the finest English and American Wiltons, moquettes and velvets, and a great variety of body brussels, tapestry brussels, Westminster, Agra, and extra superior ingrains. The display of rugs embraces the most exclusive line of Turkish, Persian, Indian, Japanese, Smyrna, Berlin, Axminster, Wilton, and fur rugs,” according to a Sunday Herald article from 1891. “The department of fur rugs is one of special interest,” the Daily Critic had previously noted, with “skins of raccoons, wild cats, black bears, wolves, and foxes forming picturesque floor decorations.”

Advertisement from the April 18, 1915 edition of The Evening Star.

Extensions were added in 1887, 1889, and 1898, resulting in more than three and a half acres of showrooms and manufacturing space. Eventually two other warehouses and a separate manufacturing plant were established in other parts of the city. The company’s name changed to “W.B. Moses and Sons” in 1890, when Willie’s two younger brothers, Harry (1869-1928) and Arthur (1870-1949), joined the firm. The three sons carried on as equal partners when their father died after a brief illness in 1892.

It was in the same year that his father died that Willie commissioned prominent architect Franklin T. Schneider (1859-1938) to design a grand suburban villa for him on a hilltop in Kalorama Heights. Schneider created a rambling Queen Anne style villa that still stands on Wyoming Avenue NW, although much altered from its original design. After sitting vacant for many years the mansion was rehabilitated and opened as the Embassy of Macedonia in 2005. The embassy was the site of the D.C. Preservation League’s recent annual meeting.

The W.H. “Willie” Moses Home, now the Embassy of Macedonia (photo by the author).

In 1912, Arthur Moses sold his share of the company to his older brothers, leaving to focus on banking and real estate. Willie remained the senior partner and driving force behind the firm. By this date the W.B. Moses and Sons firm was a venerable Washington institution that continued to receive prestigious commissions, including the redecorating of the old Shoreham Hotel on 15th Street in 1913. The hotel wanted a complete makeover in the then-popular Colonial Revival style, and W.B. Moses produced over 2,000 pieces of mostly solid mahogany furniture and laid more than 14,000 yards of carpeting to fill the order.

The prestige of the W.B. Moses name continued through the 1920s and into the early 1930s, with the company outfitting a model Spanish bungalow for developer Morris Cafritz in 1926 and furnishing The Washington Post’s model homes in the early 1930s. But after Willie Moses died in 1931, the company’s fortunes began to sink. New managers did not understand the business well and struggled against the tide of the Great Depression. As a luxury brand known for its high prices, W.B. Moses had trouble competing for consumers’ scarce dollars.

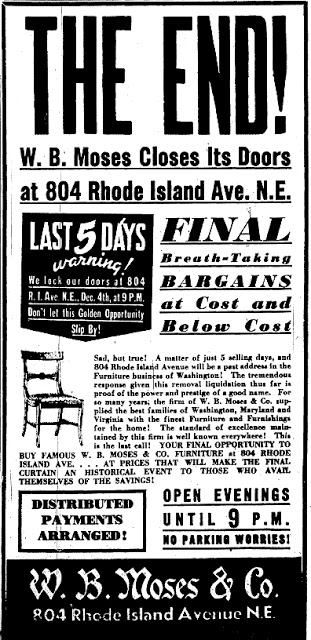

The company tried to sell its furniture at a substantial discount. In early 1936, it sold its flagship building at 11th and F Streets and moved to a warehouse at 804 Rhode Island Avenue NE. Advertising that the new location’s lower overhead meant lower prices for customers, the company offered more and more desperate discount sales events, but it was never enough.

Advertisement from the November 30, 1937 edition of The Evening Star.

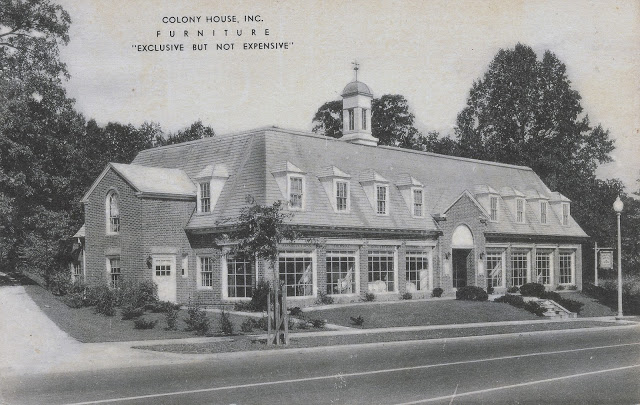

Finally in 1937 the decision was made to drop the W.B. Moses brand altogether. The company invested in a brand new Colonial Revival style showroom at 4244 Connecticut Avenue NW (where the Van Ness Metro station is now located) and organized a new company called Colony House, Inc., to focus solely on high-quality Colonial Revival furniture. The W.B. Moses Company officially closed its doors forever that December.

Postcard view of the Colony House furniture store at 4244 Connecticut Avenue NW (author’s collection).

The new Colony House company, much smaller than W.B. Moses, thrived on Connecticut Avenue and even opened a branch store on Lee Highway in Arlington in 1957. Colony House remained in business in Arlington until 2011.

The southwest corner of 11th and F Streets NW as it appears today (photo by the author).

As for the once magnificent Moses Building at 11th and F Streets, its glory days were over once the W.B. Moses Company left. The building was sold at auction for $800,000, and the new owners rented it out as office space with shops on the first floor. In 1941, shortly before Pearl Harbor, the U.S. General Accounting Office leased all of the office space, some 93,000 square feet, to house 575 workers in its Audit Division. The auditors stayed until 1948. Then in 1954 the building was torn down and replaced with a large parking garage. This strikingly unattractive structure was finally removed in the mid 1990s, when a large, post-modern office building, filling the entire block, took its place.

* * * * *

Special thanks to Jessica Smith of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., for her very efficient assistance. Additional sources for this article included James Goode, Capital Losses (2003); Washington, D.C. With Its Points of Interest Illustrated (1894); Who’s Who in the Nation’s Capital (1921); and numerous newspaper articles.

Recent Stories

Photo by Beau Finley Ed. Note: If this was you, please email [email protected] so I can put you in touch with OP. “Dear PoPville, Him, dapper chap with a light…

For many remote workers, a messy home is distracting.

You’re getting pulled into meetings, and your unread emails keep ticking up. But you can’t focus because pet hair tumbleweeds keep floating across the floor, your desk has a fine layer of dust and you keep your video off in meetings so no one sees the chaos behind you.

It’s no secret a dirty home is distracting and even adds stress to your life. And who has the energy to clean after work? That’s why it’s smart to enlist the help of professionals, like Well-Paid Maids.

Unlock Peace of Mind for Your Family! Join our FREE Estate Planning Webinar for Parents.

🗓️ Date: April 25, 2024

🕗 Time: 8:00 p.m.

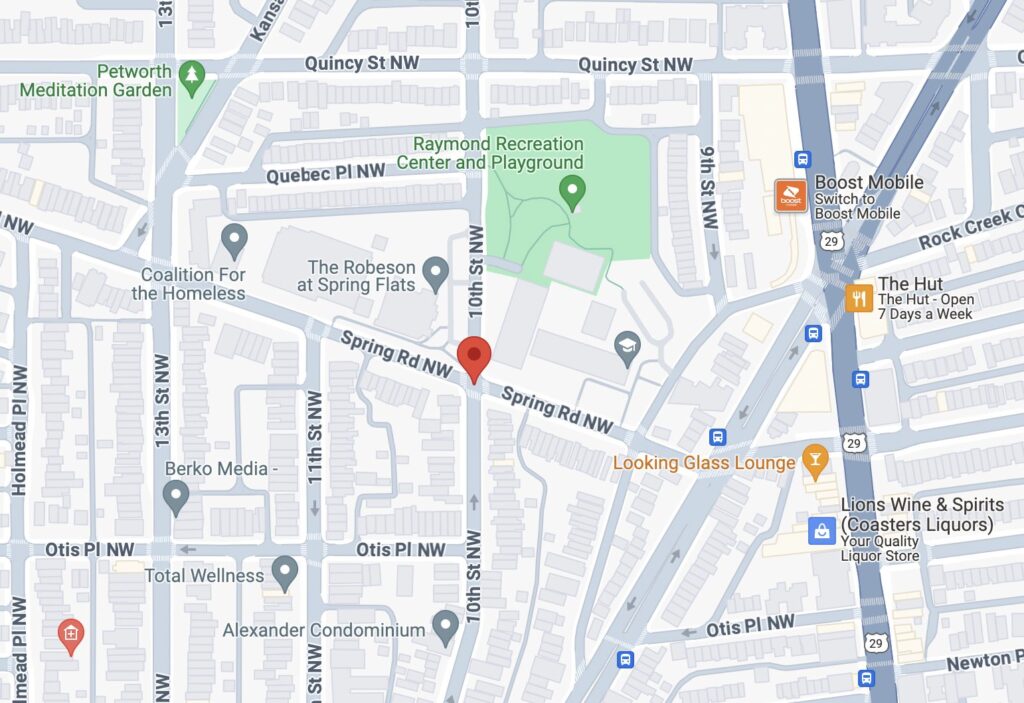

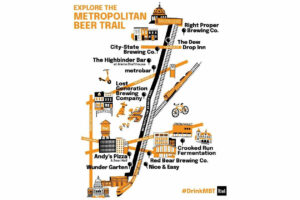

Metropolitan Beer Trail Passport

The Metropolitan Beer Trail free passport links 11 of Washington, DC’s most popular local craft breweries and bars. Starting on April 27 – December 31, 2024, Metropolitan Beer Trail passport holders will earn 100 points when checking in at the

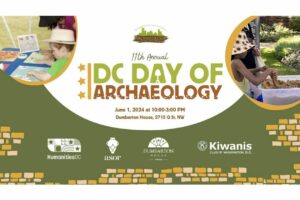

DC Day of Archaeology Festival

The annual DC Day of Archaeology Festival gathers archaeologists from Washington, DC, Maryland, and Virginia together to talk about our local history and heritage. Talk to archaeologists in person and learn more about archaeological science and the past of our